By David Bressoud @dbressoud

As of 2024, new Launchings columns appear on the third Tuesday of the month.

The 2025 CBMS Survey is currently underway. This survey of mathematics and statistics

department in the United States has been conducted every five years starting in 1960 and

provides important information on practices and trends in undergraduate education in the

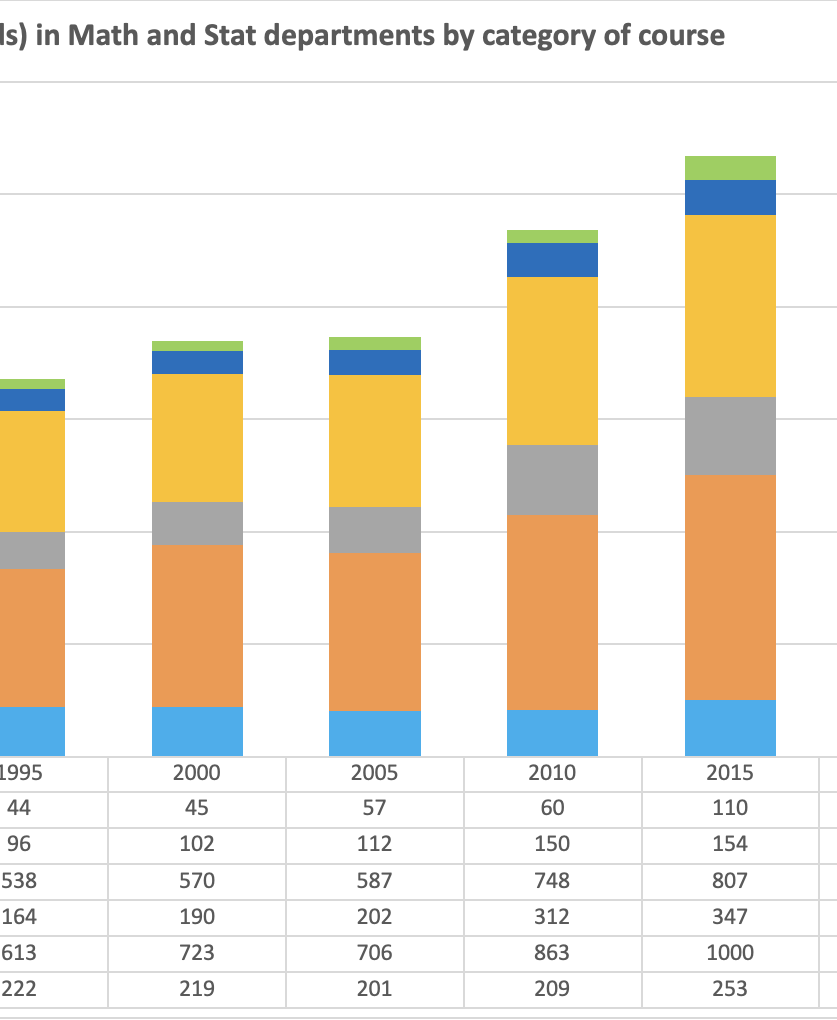

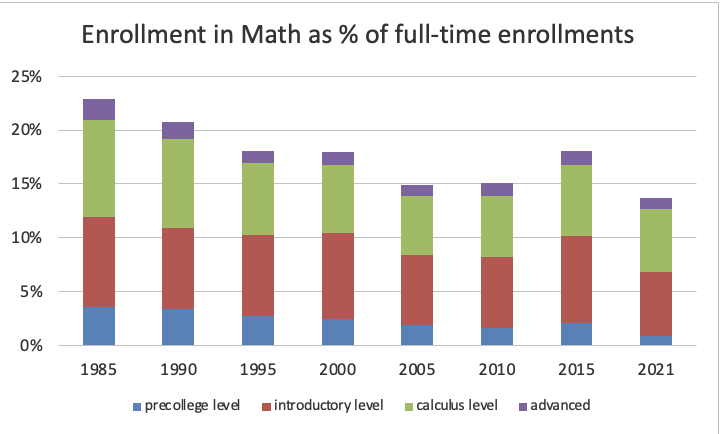

mathematical sciences. As one example, Figure 1 shows data from 1985 through 2021 (a

postponement of the 2020 survey because of COVID) that reveals a large-scale decrease in

math department course enrollments. Total enrollments grew sharply from 2005 to 2015,

but then dropped off sharply by 2021.

The decrease in Precollege mathematics was particularly precipitous, due to a documented trend to offload Precollege courses to 2-year institutions. But across the board we are looking at a loss of a fifth or more in course enrollments. One of the big questions for the 2025 survey is whether this was a temporary aberration related to the COVID epidemic or whether there is a long-term downward trend.

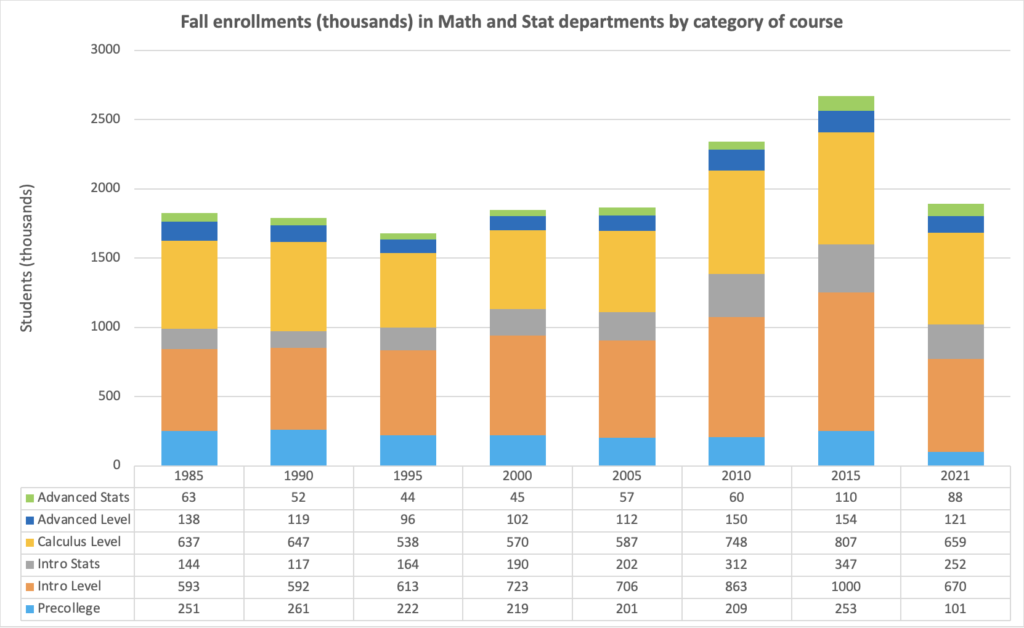

If we look at enrollments in mathematics courses as a percentage of full-time undergraduate enrollment (Figure 2), the decrease is more alarming, a downward trend that was briefly reversed in 2015 but reached an absolute minimum in 2021.

enrollment. Full-time enrollments are from the US Department of Education Digest of Education Statistics.

In view of this, it is interesting to see which courses offered by 4-year mathematics departments increased fall enrollments from 2015 to 2021, data we can glean because the CBMS survey collects enrollments by course. There were exactly three:

- Introduction to Mathematical Modeling, from 12,000 to 19,000,

- Linear Algebra, from 54,000 to 65,000,

- Vector Analysis, from 4,000 to 12,000.

The commonality among these is their usefulness in a wide range of applications, potentially helpful information for departments facing declining enrollments.

The topics that are covered in the 2025 survey include:

- Fall 2025 enrollments by course

- Dual enrollment

- Distance/Remote learning

- Non-traditional Pathways

- Use of active learning

- Intro Stats (what types of technology, use real data, use of resampling and boot-strapping, etc.)

- Required courses for major

- Future plans of grads

- Types of program assessments

- Engagement opportunities for undergrads

We have seen some confusion between the requests for data sent out by AMS and the CBMS survey. AMS collects data on the faculty. Strictly speaking, theirs is a census, not a survey, since it goes to every department of mathematics in the U.S. Every department should have received the AMS census. Only the randomly selected departments received the request to fill out the CBMS survey. Both their faculty census in the years of the CBMS survey and the results of the CBMS survey are published together in the Statistical Abstract of Undergraduate Programs in the Mathematical Sciences in the United States, available at www.ams.org/learning-careers/data/cbms-survey. Traditionally, the AMS faculty census has been sent out every year, but COVID and staff changes have interrupted it. AMS is restarting it for 2025–26.

But we have a problem. Response rates to this data collection have been abysmal. Up through 2015, participation in the CBMS Survey ranged from 60% to just above 70%. The current survey was sent out in October with a requested response by early November. By December, only 15% of the selected colleges and universities had responded.

It is not too late to collect 2025 data. You can access spreadsheets with the list of the institutions selected for our survey, the people we have tried to contact at each institution, and whether we have been successful in making contact. There are separate spreadsheets for the 4-year mathematics departments available at https://tinyurl.com/4yearcontacts, the 2-year mathematics departments available at https://tinyurl.com/2yrcontacts, and the departments of statistics with undergraduate programs available at https://tinyurl.com/statcontacts. Any help in making contact and getting timely responses from the departments for which we have not yet had any response will be greatly appreciated.

There are three separate CBMS Surveys: one to departments offering full 4-year undergraduate programs in mathematics, one to 2-year colleges, and one to departments of statistics offering undergraduate programs. To request access to any of the surveys, you can use the following QR codes:

4-year Math Departments

2-year Math Departments

Stat Departments

David Bressoud is DeWitt Wallace Professor Emeritus at Macalester College and former Director of the Conference Board of the Mathematical Sciences. Information about him and his publications can be found at davidbressoud.org