By Lew Ludwig

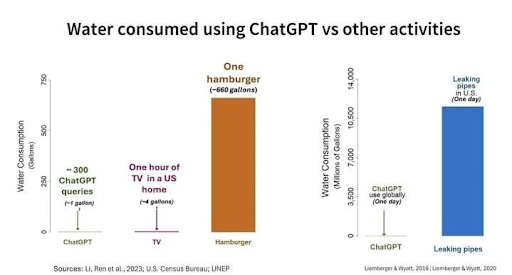

The hamburger graph has become my unexpected companion this summer. It first appeared in a workshop I was co-facilitating, comparing the water usage of AI prompts to beef production. Then it surfaced again a few weeks later - and that's when I realized we weren't really arguing about water at all.

The first time, an educator studied the comparison carefully. "What they're hiding," they said, pointing at the chart, "is the difference between green water and blue water. AI cooling uses treated drinking water. That cow? Mostly rainwater from ponds and streams."

The second instance came in another workshop. This time, a participant who'd been quietly observing in that first session looked at the same graph with visible relief. "See? Eating a hamburger is way worse than using genAI."

They'd heard the green water argument. They knew the counterpoint. But the graph still offered them what they needed: permission to stop feeling guilty about the AI tools they'd already integrated into their teaching.

This wasn't about water. It never was.

The pattern extends beyond graphs. During another workshop this summer for mathematicians, one participant dismissed environmental concerns entirely: "Energy consumption in the US has been flat for a decade. What AI is exposing is not a concern of energy consumption, but a need for updated electrical infrastructure."

The aggressive certainty puzzled me until post-workshop investigating revealed the source: a tech CEO who'd somehow joined our educator session. The mismatch explained everything—someone with money riding on AI, in a room of educators grappling with classroom implications.

Then in a community Zoom, a faculty member—exhausted from battling copy-paste solutions from ChatGPT—offered the opposite: "AI is horrible for the environment. I'm not sure of the numbers, but each prompt uses large amounts of water and electricity."

Notice the revealing details: The CEO pivots to infrastructure without addressing the actual question. The faculty member admits uncertainty about the very numbers they're citing. Both had already chosen sides; the environment was just ammunition.

What we need isn't more soapboxes—it's a table sturdy enough for disagreement and curiosity alike. But before we can gather there, we have to name the habits that keep us apart.

Take, for instance, how the deflections come fast when environmental concerns are raised: "But what about streaming Netflix?" "What about flying to conferences?" "What about Zoom calls?" These aren't entirely wrong - a single transatlantic flight does dwarf months of AI usage. But this whataboutism reveals we're not really having an environmental discussion.

I'll admit, I've reached for these arguments myself. When colleagues dismiss AI because of environmental concerns without trying it, I find myself countering with "But what about Netflix?" When I catch myself doing this, I know it's not really about water usage—it's about my frustration that we're not even having the real conversation.

Meanwhile, those citing environmental concerns often can't remember the actual numbers. What they're really defending is the status quo - a system that, honestly, was already failing. Roll back to 2021, before ChatGPT entered our classrooms. Were take-home assignments actually working? Students had Chegg, Stack-exchange, and a cottage industry of homework "help" sites. We were already playing whack-a-mole with academic dishonesty. GenAI didn't create this problem - it just accelerated it, stripping away our ability to pretend the old methods worked.

I know I'm going out on a limb here. Literally, if you look at this month's illustration - there I am, the anxious hobbit creeping along a branch while others below shout from their respective soapboxes. One stands firmly on "Whataboutism," the other on "Status Quo," and between them looms the strawman with "Environment" emblazoned on its chest - the argument they're both attacking instead of addressing what's really at stake.

The environment matters. Of course it does. But when we use water usage statistics we can't quite remember, or pivot to infrastructure arguments to avoid the question entirely, or interpret the same data through whatever lens supports our predetermined position, we're not really having an environmental discussion. We're using environmental language to fight about something else entirely: our discomfort with how quickly AI is reshaping education, our fear of being replaced, our exhaustion with constant technological change, or our excitement about new possibilities.

I see this as an all-hands-on-deck situation. We should be meeting around the table, not retreating to our corners. Generative AI is the most disruptive force education has experienced in our lifetimes. It hasn't just upended how students complete assignments or made us question our roles as educators - it's rapidly changing the very economy our students will graduate into.

We cannot afford to bury our heads in the sand and refuse to engage with AI because of environmental concerns, nor can we throw up our hands with whataboutist deflections. Both stances surrender our agency in shaping how these technologies will be used by us, our students, and our institutions. We need diverse voices at the table as we chart our path forward.

This brings me back to Freire and Shor's insights in Pedagogy for Liberation. They understood something crucial: challenging oppressive systems requires more than critique—it demands that we equip students with the tools to navigate those very systems. Our discomfort with teaching AI doesn't protect students; it abandons them. They'll enter a workforce shaped by these technologies whether we prepare them or not. The choice isn't whether they'll encounter AI, but whether they'll face it with understanding or ignorance.

So how do we get from critique to constructive practice? For me, it starts with small, sustainable routines.

I return to Marc Watkins's framework for "a sustainable plan to bring you up to speed on a technology that academe can't afford to ignore." Set aside a weekly 90-minute routine: 30 minutes exploring these tools, 30 minutes reading about them, and 30 minutes reflecting on what you've learned. That reflection is especially powerful when done around the table with diverse perspectives, learning from one another's experiences.

For your reading, while The Chronicle (where Marc has a column) and Inside Higher Ed offer solid coverage, Stephen Fitzpatrick recently argued that "The Real AI in Education Debate Is Happening on Substack"—and I tend to agree. In his piece, he recommends ten educators worth following and explains how to find others. I'll second his picks of Marc Watkins and Ethan Mollick for thoughtful, nuanced takes on AI in education.

For exploration, start with the big three: ChatGPT, Gemini, or Claude. Most of us have free ChatGPT accounts, which now include access to the advanced 5.0 model for 10-15 queries per five hours. Google campuses may have Gemini 2.5 Pro access. Whatever you use, test it in your area of expertise so you can critique its output effectively. Pro tip: when it gets something wrong, treat it like a student who gave an incorrect answer—guide it toward better understanding with follow-up questions.

And those conversations around the table? Unlike our battles with Chegg or Stack Exchange—traditional math education problems—generative AI affects everyone. Don't limit yourself to math colleagues. Friends in English are grappling with AI-written essays. Scientists are questioning lab reports. Artists are debating creative authenticity. Pull up a chair and learn what they're discovering.

The environment matters. The disruption is real. But using these as weapons in a proxy war helps no one. Our students need us present, engaged, and honest about the challenges ahead—not retreating to our corners, armed with arguments we half-remember about water usage or whatabout airlines.

Time to climb down from that limb and gather around the table.

AI Disclosure: This column was created using the AI Sandwich writing technique, with Claude serving as a collaborative editor. I brought the raw observations from my workshops, the initial framework, and the core argument about environmental strawman. Claude helped structure the narrative flow, refine transitions, and polish the prose while maintaining my voice. The experiences, opinions, and that precarious hobbit on the limb? All mine. The editorial refinement that helped me avoid overdoing the metaphors this time? That's where AI proved useful.

Lew Ludwig is a professor of mathematics and the Director of the Center for Learning and Teaching at Denison University. An active member of the MAA, he recently served on the project team for the MAA Instructional Practices Guide and was the creator and senior editor of the MAA’s former Teaching Tidbits blog.