By David Burn

https://www.pexels.com/photo/a-motivational-quote-and-an-abacus-15506749/

From axioms come idioms.

In the past, I have clumsily claimed that I’m not good at math, but that’s like being not good at gravity. Everything relies on math. Science and engineering rely on math. Language relies on math. Mathematics is the structure underlying our primary ways of thinking and making sense of the world. We have 26 letters to express an infinity of ideas, from the scientific to the poetic. Likewise, western music contains just 12 notes, and artists from punk rock to classical to blues and jazz play by its rules.

One could argue that musicians, writers, and others are better at math than they may realize. We just don’t think of it as math. In other cases, the control math has over us is obvious. For instance, when we’re “on the clock,” we are ruled by math.

Math is also embedded in our language. You can hear it in everyday idioms like “go figure,” “divide and conquer,” and “back to square one.” In these common phrases, you can also hear the importance that we place on math. We reveal ourselves in language. Our word choice and phrasing might appear to be casual or random, but that’s often not the case. Language conveys intention. For instance, when someone says “do the math” or “run the numbers,” they’re suggesting that the answers they seek reside in an unsolved equation.

Why do we place so much faith in math? Is it because math seems so certain, and we’re all grasping for certainty? Maybe, but according to my research, uncertainty is also part of mathematics. Different axiom sets, like Euclidean versus non-Euclidean geometries, lead to different but equally consistent mathematics. In Euclidean geometry, parallel lines never meet; in hyperbolic geometry, they do. In addition, Kurt Gödel’s incompleteness theorems show that within any sufficiently complex system (like arithmetic), there are undecidable statements that are neither provable nor disprovable within that system itself. This means mathematics is inherently incomplete—there’s always something left uncertain.

And how does uncertainty make us feel? I know from a career working in advertising agencies that uncertainty is rarely welcome. Clients with budgets to protect are often obsessed with measurement and return on investment—a form of perceived certainty that they can get behind, explain to their bosses, and keep their jobs. Whereas creativity is considered subjective and notoriously difficult to quantify.

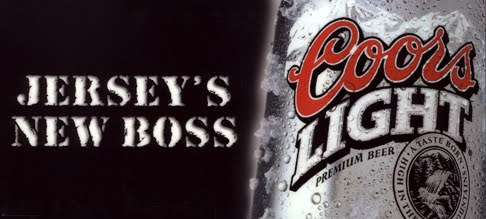

Let me tell you a story about a regional billboard that I made for Coors Light. The assignment was to highlight how the brand had surpassed Bud Light as the number one selling beer in all of New Jersey. The local distributor wanted to say exactly that on the billboard; after all, it was big news that they were eager to share. After working the problem over, I was “equal to the task” and delivered the winning headline, “Jersey’s New Boss.”

When I wrote the billboard for Coors, I knew it needed five words or fewer in the headline, or it would be illegible at high speeds. I’ve written several billboards, and it’s a challenge to say something memorable and flattering to a brand in under six words. In this case, being constrained by the media environment and ruled by math was a gift. To turn a factual statement into a persuasive statement, it helps to think like a poet.

Poets routinely work within the confines of mathematical formulas. A sonnet is a poem with 14 lines, typically written in iambic pentameter (a rhythm with 10 syllables per line) and following a specific rhyme scheme. Shakespeare mastered the sonnet. He was good with math.

Poets are also masters of “less is more.” Haiku writers are limited to the use of five syllables on the poem’s first line, followed by seven syllables on the second, and five on the third. That’s just 17 syllables, and yet much can be said in a haiku. Pi-kus are even thriftier, allowing just three syllables on the first, the second with one syllable, and the last with four. As in, 3.14.

Here's a haiku I penned for this occasion.

Prickly Pear Cactus

The flowering survivor

Resilient Native

How we present our facts and make our case matters. For instance, an article’s word count is critical. Online, we have endless column space, but we can never count on endless fascination from readers. Hence, we limit our word counts to something reasonable (unless we’re writing for The New Yorker). This essay is just over 800 words long and can be read in about five minutes. To “measure up” as an essayist and work within the limits of this narrative math, I must employ an economy of language and make my most cogent points readily available.

Maybe it’s time to remind ourselves that our best writing, art, and music are all reliant on math. When we recognize a distinct but familiar shape, or hear a pleasing rhythm and rhyme, the art is speaking to us in our language, and more often than not, that language—our structure for conveying meaning—is mathematical.

David Burn is a writer, brand strategist, and creative director with content marketing expertise and experience working closely with the decision-makers at Fortune 500 companies, spunky startups, family-owned businesses, and a variety of good causes. He’s the founder of Adpulp.com, one of the first advertising blogs on the scene. He also writes a free monthly newsletter for writers, artists, and entrepreneurs who like to stir it up.