By Keith Devlin @KeithDevlin@fediscience.org, @profkeithdevlin.bsky.social

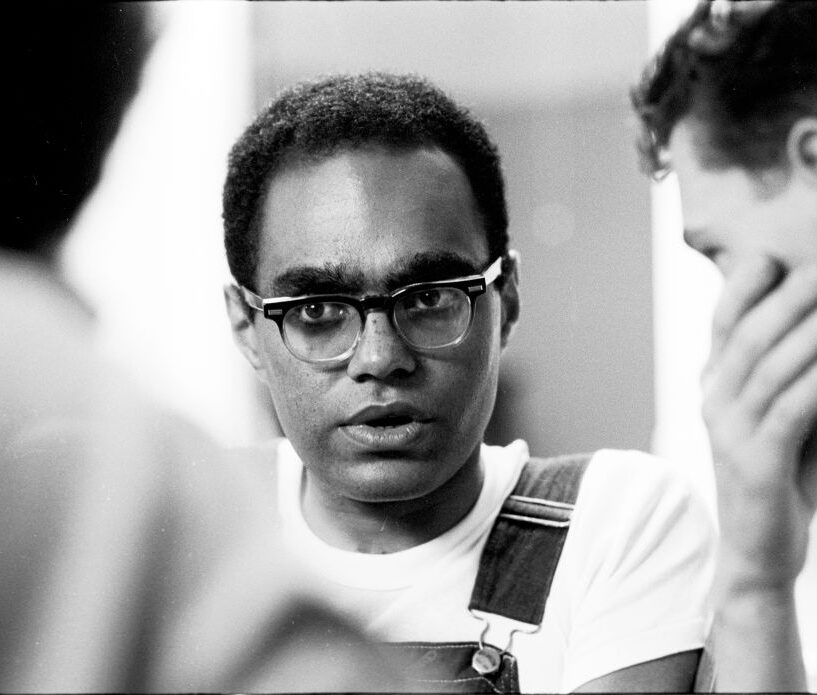

My July 2024 Angle post focused on the newly released documentary movie Counted Out, for which I was pleased to have been an advisor. One of the math educators featured in the film was the legendary Bob Moses, who died in 2021.

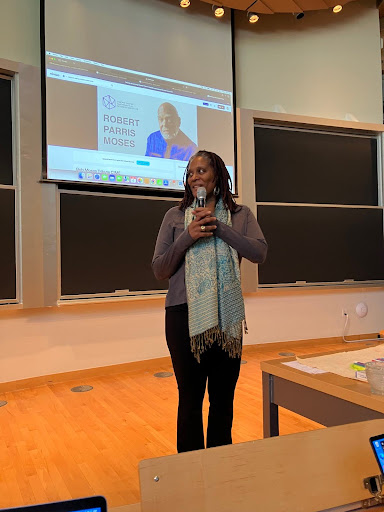

Moses was someone I always wanted to meet, but somehow never managed it. Although I did meet his daughter Maisha Moses, also a math educator, at a workshop in Berkeley recently.

Berkeley (formerly MSRI) / Photo by Keith Devlin

To my generation, Moses is well known. If you’re reading this and are not familiar with his work, this short video related to his 2021 NCTM Annual Meeting Closing Plenary, “Math Literacy as a 21st Century Civil Right,” should bring you quickly up to speed.

You can find out about the Algebra Project, which he created, in this short video.

Plus, there is the coverage in Counted Out.

Also, you can learn about his more general political activism in the documentary Eyes On The Prize (Part 1): Awakenings 1954-1956 America's Civil Rights Movement.

Those of us born in the west in the post-World War II era have lived our entire lives in a society where education is not only literally taken as a right, but we find it self-evident that it should be so. We know it’s how society advances and people’s lives get better. To a great extent, that state of affairs was a result of the Cold War. Both Britain, where I was born, raised, and educated, and the USA, where I have lived since 1987, had aggressive research programs in science and medicine, and aggressive STEM-focused national education programs, in order to have the knowledge and the people to defend against aggression by the Soviet Union.

On the other hand, that thrust had a narrow focus. It was all about STEM. As part of the leading-edge boomer generation, for me, in the UK, high school beyond 16 was just an available option to be acquired competitively against my peers, and universities took just 3% of the student-age population. I got both, most did not. But the two elite universities, Oxford and Cambridge, required a qualification in Latin for entry, which was not an option for me. I and every other child from a working class home were “counted out” by Oxbridge.

By the time my own children were growing up, education through university really was available to all, in both the UK and the US (at least California, which is where I brought them when I fled the UK in 1987).

There had been a brief but strong anti-education movement in the UK relatively early in my academic career, which is what led me to decamp to the United States. (Half of my UK mathematics department left in a two-year period, mostly to English-speaking countries. Mathematics was viewed as low-hanging fruit to be axed; something else that I found staggering, in an era when mathematics was beginning to creep into everything.)

As Moses so eloquently pointed out repeatedly throughout his long career, the kind of education nations provide their citizens is a political choice.

The US had long provided many of its citizens what Moses called “sharecropper education.” Much of his work was aimed at changing that. That change did come, was largely made possible by the Cold War, mentioned earlier, which forced the US to develop, quickly, a science, technology, and engineering workforce as good as any in the world.

In the 1980s, I learned to my surprise that many of my fellow Brits did not at all think quality education designed to prepare students for life and work was a wise way to spend taxpayer money. A basic “3 Rs” education – reading, (w)riting, and ‘rithmetic – was all that people needed, they asserted. A view based, I presume, on the fact that such was what previous generations had received, and it was good enough to prepare them for life when they started out.

And now here, in the US, we have an entire political party that won (small, but across-the-board) majorities on an aggressively anti-science, anti-education platform. (Also anti-public-health, which was new in my experience. I am from the generation many of whom survived because of mass vaccination programs.) Sharecropper education seems to appeal to those who now call the shots in DC.

The UK came through its onslaught on education in moderately good shape, and over time rebuilt what had been cut. The outcome here in the US is by no means clear. The destruction has already been much more severe, and most of the plan has yet to be implemented. But Americans have lived their entire lives with all the benefits of science, education, and world-class health services (albeit the latter are distributed extremely unevenly). They may rebel when they discover how bad things can be without that support structure they’ve never had to think about. It was just “there.”

In the meantime, those of us in the US education world have to accept that, right now, our elected government does not believe we have the societal value we thought we did.

As Winston Churchill reportedly said (and I give a US-slanted paraphrase), “democracy sucks, but the other systems of government are much worse.” The US system has a particularly unrepresentative system of democracy, which stems from its history as a very young nation. But, within that system, the people have, indeed, spoken. They may, of course, change their mind. People do. (I do it all the time. In fact, mathematics forces you to accept that in some circumstances we are wrong far more often than we are right.)

We each, of course, have to decide what, if anything, to do in response, both individually and perhaps collectively. Moses did (in his time). And his success shows just how much difference a single voice can make, provided the message is good and well-articulated.

One thing we should do, as scientific and educational professions, is ask ourselves if we did not do enough to make our fellow citizens aware of the societal benefits we know we provide. When, in the 1980s, a local business leader in the UK I knew fairly well (we did 20 mile runs together every Sunday morning) told me to my face that my university was overstaffed and low on productivity, I realized we had a problem. We weren’t. He was viewing us purely as a production line with students the raw material passing through to have value added, and doing some simple arithmetic. He had no idea universities are one of society's major engines of innovation and providers of valuable information to live our lives. It was one of the factors that propelled me to engage in science outreach activities.

Do check out Bob Moses, if you are not already familiar with him. It’s an impressive story about a remarkable American.