By Lew Ludwig

May has felt like a whirlwind of workshops and webinars on AI in education, including the MAA OPEN Math series and an online short course for the Ohio MAA. It was great connecting with colleagues who actually understood my well-worn jokes about extroverted mathematicians staring at their own shoes. Amidst the flurry of discussions and demonstrations, two themes consistently rose to the surface: the charm of chatbots and the specter of environmental concerns. In hindsight, these themes aren’t just academic curiosities—they’re signs of the educational crossroads we’re navigating.

Chatbots: The Novelty with Nuances

Chatbots—those clever little conversational agents powered by generative AI like ChatGPT, Claude, or Gemini—have quickly captured educators’ imaginations. It’s understandable. Who wouldn’t be tempted by the promise of a digital Socrates, tirelessly guiding students through quadratic equations or integration by parts at any hour?

Yet, as much as I'd love to join the enthusiastic chorus, I'm hesitantly humming along. Sure, chatbots are infinitely patient and perpetually available, seemingly the perfect tutors. But beneath their shiny surfaces, challenges lurk. They’re notoriously distractible—one minute you can get algebra help, and the next a recipe for a decent martini. Effective guardrails, especially for "homemade " chatbots using platforms like ChatGPT's custom GPTs, remain elusive. Commercial solutions like Khanmigo or Magic School AI offer better boundaries, but at a cost. Sometimes the price isn't just money; it's your students’ privacy and agency handed over in exchange for convenience.

Most importantly, there’s a subtle erosion of genuine human interaction. The warmth of real-time mentoring, the spontaneous humor in classroom discussions, even the inevitable imperfections in teaching—all of these are part of what makes learning feel human and worth showing up for. A chatbot might explain completing the square perfectly every time, but it won’t understand the subtle cues signaling confusion, frustration, or sudden insight.

So yes, chatbots are impressive and useful—like having a kitchen gadget that slices avocados perfectly. But do we really need another specialized tool crowding our drawers, particularly when our trusted chef’s knife still works wonders?

Climate: A Bigger, Murkier Picture

If chatbots are kitchen gadgets, our environmental worries are the kitchen's clunky old blender—loud, hard to ignore, and always buzzing just beneath the surface of every AI conversation. Our workshop discussions addressed the environmental toll of generative AI. Consider this striking statistic: a single series of 5 to 50 AI prompts can use approximately 500 milliliters of water—a number that varies widely depending on model, prompt length, and system infrastructure. Visualize it as a single disposable water bottle—the environmentalist’s quintessential nemesis.

Yet, perspective matters here. The average American consumes around 80 gallons of water daily; by comparison, 500 milliliters makes up just 0.165% of that. A drop in the (very large) bucket. This doesn’t absolve AI companies; it merely illustrates that individual guilt might be misplaced. Rather, we should direct our concern toward systemic issues like the rapid proliferation of data centers, largely driven by AI—both the generative kind, like chatbots and image creators, and the more traditional algorithms powering recommender systems, enterprise analytics, ad targeting, and computer vision. In fact, these traditional applications account for the majority of AI's energy use in data centers. As an insightful MIT report points out, not every AI-driven data center expansion is justified or sustainable.

Still, there’s no value in self-flagellation over every AI-generated image or chatbot interaction. Andy Masley succinctly reminds us that personal guilt rarely drives systemic change. The challenge is to balance mindfulness about our digital footprints with a clear-eyed view of where impactful interventions truly lie.

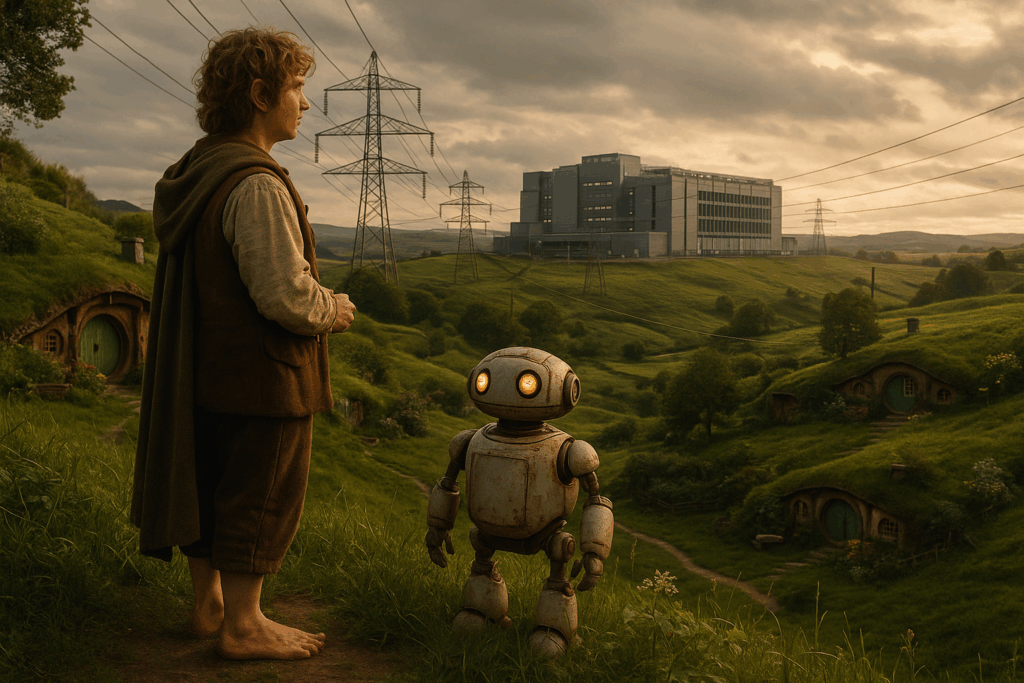

For educators, these murky trade-offs are more than talking points—they’re teachable moments. Like Bilbo venturing reluctantly but wisely into the unknown, we educators find ourselves at the crossroads of curiosity and caution. That sense of adventure—equal parts awe and anxiety—feels familiar. But unlike Bilbo, we’re not looking for gold or glory. We’re seeking insight, understanding, and perhaps a little wisdom to bring back to the classroom.

And here's our special strength as mathematicians: we transform uncertainty into clarity. Imagine, for instance, a quantitative reasoning course that actively investigates the uncertain data around AI energy consumption. Students could grapple with slippery numbers, confront the complexities of environmental impact, and emerge equipped to critically evaluate information. Such a course wouldn't merely offer mathematics as an abstract exercise, it would ground learning in urgent, real-world dilemmas, challenging students to become skilled problem-solvers as well as thoughtful participants in society.

The possibilities are compelling: students exploring real data sets, modeling scenarios to predict outcomes, and critically assessing claims that shape public debate. They might analyze water and energy use, compare systems, and question the assumptions behind those numbers. In navigating these challenges, they'd learn to appreciate mathematics not as a purely academic pursuit, but as a practical toolkit for navigating ambiguity and informing meaningful choices. What better way to prepare students to engage thoughtfully with the complex and often ambiguous world they'll inherit?

What’s new?

Frodo’s journey in The Lord of the Rings took 13 months to complete—coincidentally, almost the same amount of time since I first wrote about my student John exploring how he productively partnered with AI to understand calculus. Back then, I believed we were charting a sustainable path forward, showing how students and AI could collaborate meaningfully in the learning process.

This past week, I fed my supposedly "cheat-proof" test to ChatGPT's newer o3 model. The results? Solid B- work on the first try with a fairly simple prompt. My pride took a hit. But honestly, I should have seen this coming—I've been preaching for over a year that you simply cannot AI-proof work done outside the classroom. The technological inevitability finally caught up with my stubborn optimism.

What troubles me more than my fallen test, though, is the arms race this creates. Students get better at prompting; faculty scramble to build higher walls. It's becoming an academic Hunger Games, with each side trying to outsmart the other while the real learning gets lost in the battle. Meanwhile, the tech companies play the role of the Capitol, continuously releasing more powerful models without regard for the educational chaos they unleash, then sitting back to watch the districts—er, campuses—struggle to adapt. We're spending more energy on detection and prevention than on education itself.

Perhaps it's time to stop fighting against AI and start figuring out how to live productively alongside it. John’s patient, three-hour exploration wasn’t just good pedagogy—it might be our only sustainable model. Instead of teaching students to outmaneuver our defenses, maybe we should teach them to think in ways that make those defenses irrelevant. After all, the most meaningful learning has never been about beating the system; it's been about understanding the world deeply enough that shortcuts become unnecessary.

But how do we pull this off? We need to rebuild trust between students and faculty, helping both sides remember what we're really after. Students need to understand that learning requires friction—that intellectual struggle isn't a bug in the system, it's a feature. But faculty need to create experiences worthy of that struggle, designing challenges that feel meaningful rather than arbitrary, and showing students why the journey matters as much as the destination. Just as muscles grow stronger only under resistance, minds develop resilience and depth only when they grapple with genuine difficulty. The AI can provide the answer, but it can't provide the understanding that comes from wrestling with the question—and we need to make that wrestling feel like exploration, not punishment. And isn't that what education is ultimately about—developing minds capable of building a better future, not just finding faster solutions?

AI Disclosure: Crafted with the AI sandwich method—my voice, AI-assisted, and human-edited. AI shaped the phrasing, not the thinking.

Lew Ludwig is a professor of mathematics and the Director of the Center for Learning and Teaching at Denison University. An active member of the MAA, he recently served on the project team for the MAA Instructional Practices Guide and was the creator and senior editor of the MAA’s former Teaching Tidbits blog.