Keys to Mathematical Treasure Chests: Classroom Slide Rules

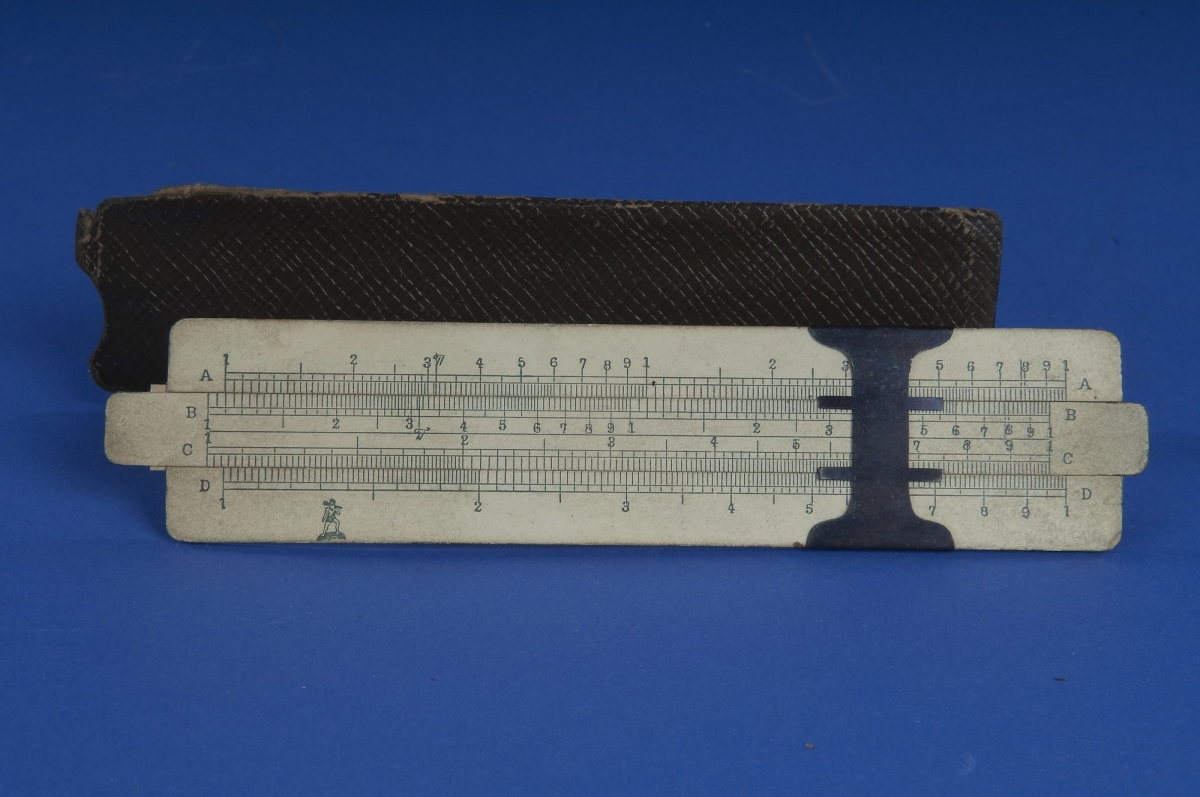

Slide rules are analog calculating devices that were invented in the 17th century, in part to aid with computing logarithms. Slide rules typically consist of a top and bottom frame with a sliding middle piece. All three parts are marked with scales. In general, a user chooses the two scales needed to solve an equation (one of which is on the slide), moves a transparent viewer called a cursor and marked with a guideline to the first value in the equation on the scale on the frame, moves the beginning point on the scale on the slide to be adjacent with that value, looks at the second value in the equation on the scale on the slide and moves the cursor to that point, and reads the solution from the adjacent point on the scale on the frame. The moving slide helped inspire the slide rule’s nickname of “slipstick”.

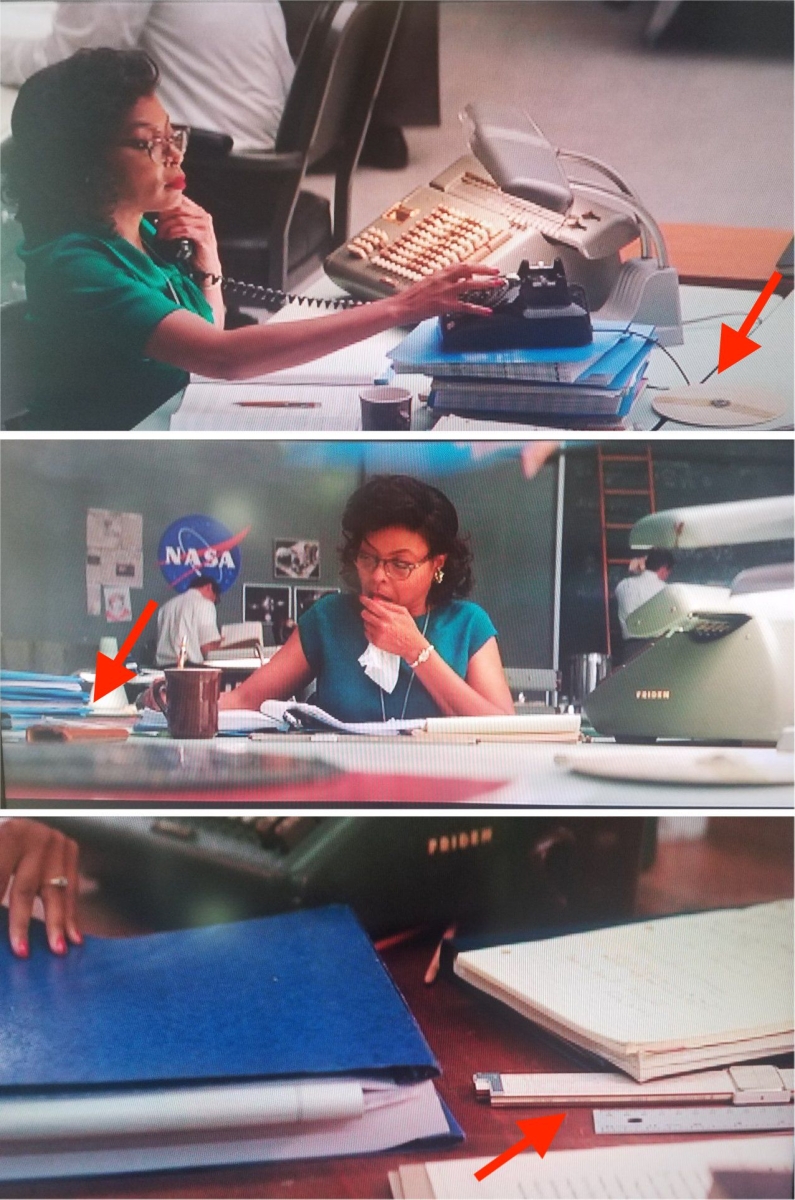

Slide rules remained in continuous use for over three centuries, but they were most widely adopted from about 1890 to 1970, when they were essential aids for the full range of engineering disciplines as well as for professionals in fields from applied mathematics to manufacturing and sales to finance. They then disappeared very quickly, thanks to the advent of electronic calculators, to the extent that anyone born after about 1980 might have seen them only in films about topics such as space exploration. For instance, the online International Slide Rule Museum’s gallery of “people with slide rules” includes screenshots from the 2016 hit Hidden Figures, which was based on the same-named nonfiction book by Margo Shetterly [Kidwell 2017].

Figure 1. Slide rules on the desks of Katherine Johnson (Taraji P. Henson) and Mary

Jackson (Janelle Monáe) as shown in scenes from Hidden Figures. Note that slide rules

did not have to be rectangular in shape—some were circular, as in the top photo, or cylindrical—and

were often stored in leather cases, as in the second photo. International Slide Rule Museum.

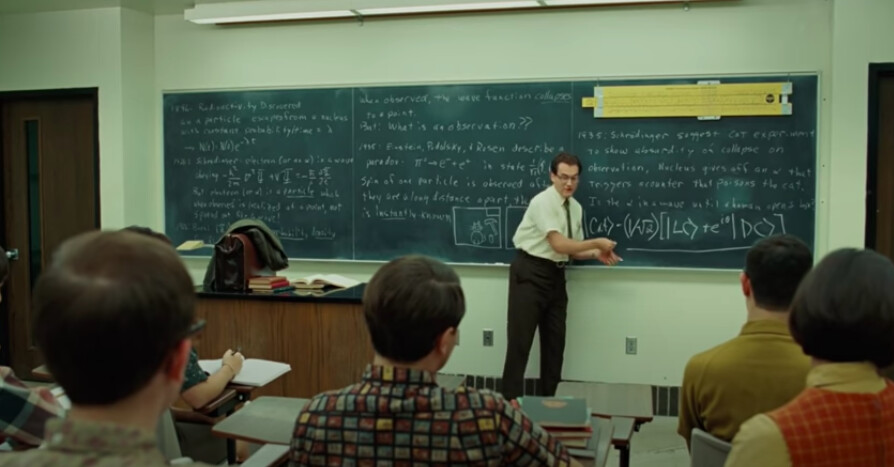

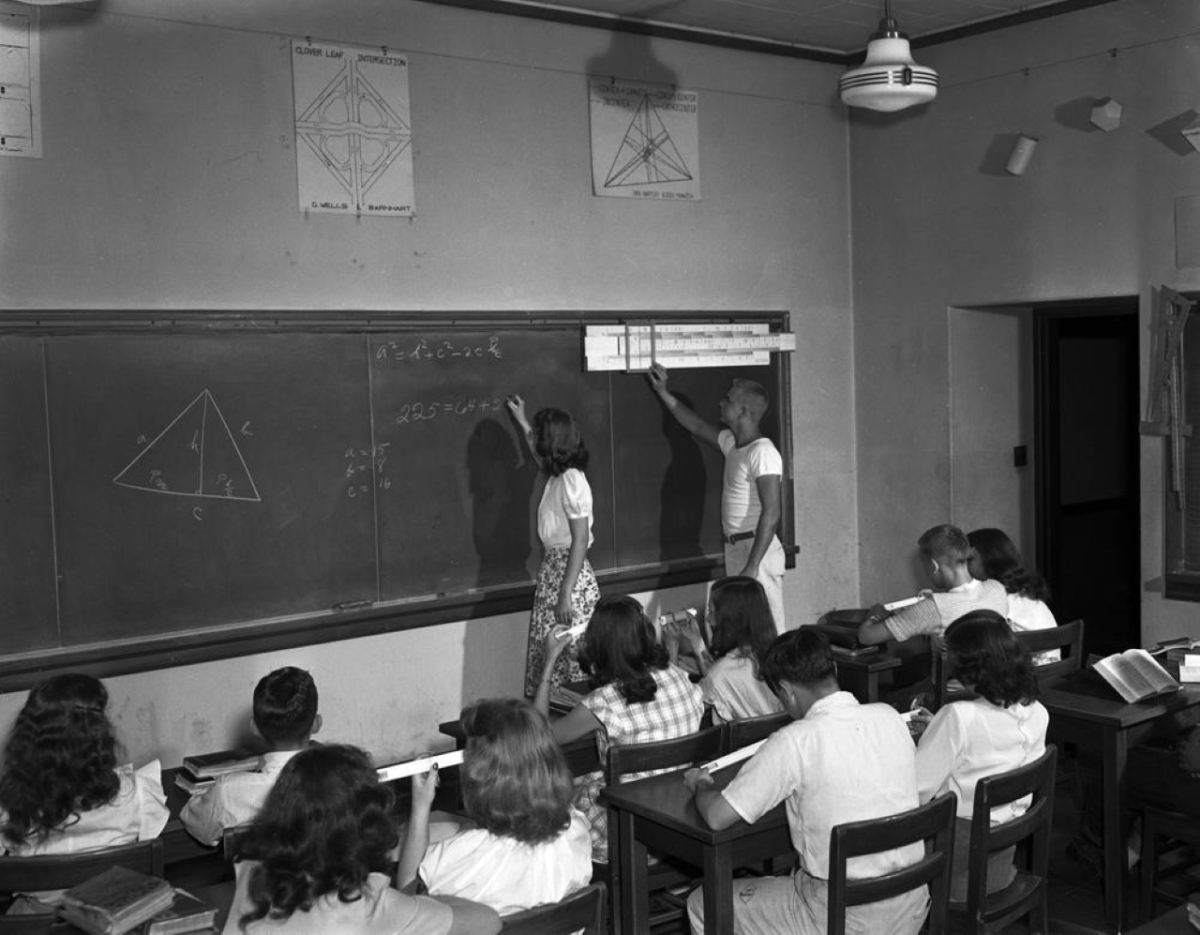

If slide rules were once ubiquitous, it stands to reason that many people were formally taught how to use them. Indeed, scenes from A Serious Man, the 2009 film written and directed by Joel and Ethan Coen, echo real-life photographs by depicting oversized slide rules used to demonstrate calculations to a class of students.

Figure 2. Above: The character Larry Gopnik (Michael Stuhlbarg) teaches a 1967 physics class with a Pickett demonstration slide rule mounted on the blackboard behind him in this screenshot from A Serious Man. Below: A demonstration slide rule (probably by Keuffel & Esser) was mounted on the blackboard in the University School mathematics class taught by Mr. Peak at Indiana University, photographed on May 8, 1947.

EdS, “Slide rules at the movies,” Retro Computing, May 18, 2021; International Slide Rule Museum.

In this installment of “Keys to Mathematical Treasure Chests,” we look at slide rules as 20th-century American high school and undergraduate students encountered them in mathematics, physics, and engineering classrooms. First, demonstration slide rules that could be mounted on walls and blackboards will be presented. Second, a few of the models designed specifically for student use will be discussed. In both cases, readers will be invited to explore online and open-access catalogues and websites containing thousands of images and descriptions of slide rules. The article will also highlight websites and emulators that offer resources for sharing this visual approach to solving equations with 21st-century students.

Keys to Mathematical Treasure Chests: Classroom Slide Rules – Rules for Demonstration

For about 200 years, slide rules in Europe were largely handmade and used mainly for specialized tasks such as carpentry and computing excise taxes on barrels of liquor. After 1850, at least three developments fostered mass production and adoption of linear (rectangular), general-purpose slide rules:

- In the instructions that accompanied his 1851 modification of a slide rule, French artillery officer Amedée Mannheim (1831–1906) suggested a selection and arrangement of scales that soon became standard, and he devised a cursor [Mannheim 1853; Cajori 1909, pp. 63–65].

- By the 1870s, German manufacturers coated wooden slide rules with celluloid (an early plastic), making them more durable and less expensive.

- Dividing engines and advanced printing techniques allowed accurate scales to be imprinted in large numbers [Ackerberg-Hastings 2012].

Figure 3. Gebr. Wichmann Mannheim Simplex Slide Rule, pre-1910.

The Mannheim scales permitted calculations of squares and square roots (A/B) and multiplication and division (C/D).

Smithsonian Institution negative number NMAH-DOR2010-0512.

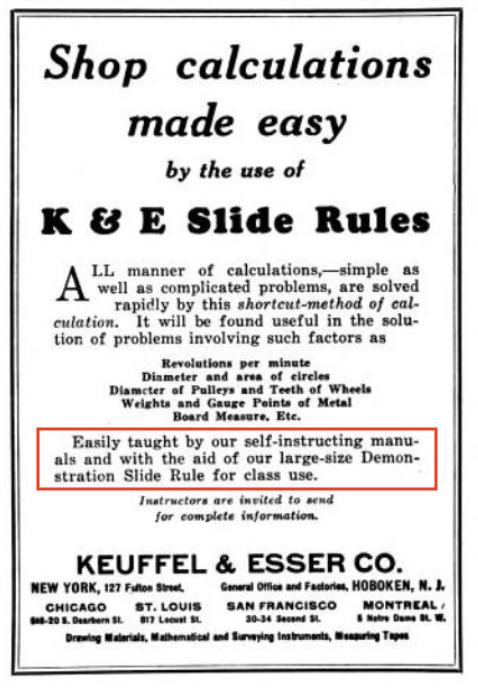

Europeans such as Adam Burg and Josef Adalbert Sedlaczek created oversized versions of slide rules that they used to demonstrate calculations in public lectures during this time period [Rudowski 2006; Kidwell and Ackerberg-Hastings 2014]. In the United States, increased demand for slide rules coincided with the professionalization of engineering occupations and the expansion of high school and college education, which meant that instruction in how to use slide rules quickly entered mathematics, physics, and engineering classrooms [Kidwell, Ackerberg-Hastings, and Roberts 2008, pp. 105–122]. By 1906, institutions such as the State College of Washington (now Washington State University) included “one Model slide rule 80 inches long” as part of the necessary equipment for their mathematics and civil engineering departments [State College 1906, p. 38]. The faculty procured this rule from Keuffel & Esser (K&E), a New York City firm that had become a leading importer of slide rules soon after its founding in 1867 and that began manufacturing its own slide rules in 1891 [Otnes 1993]. K&E was thus presumably making demonstration slide rules available from an early date, but the earliest advertisement I have found appeared in 1924 [K&E 1924, p. 27A]. It was not until 1933 that K&E listed demonstration slide rules in its catalogs and argued that they brought efficiency to teaching:

The Demonstration Slide Rule shows all the students at one time how any operation should be carried out. It saves time and reduces the cost of instruction [McCoy n.d.; K&E 1933, p. 55, emphasis in source].

Although demonstration slide rules could be purchased individually (for $8 or $15, depending on the number of scales), K&E and later companies, such as Pickett, would also provide them for free with bulk orders of regular-sized rules.

Figure 4. An early mention of demonstration slide rules (highlighted in red)

by one of the leading American manufacturers. GoogleBooks.

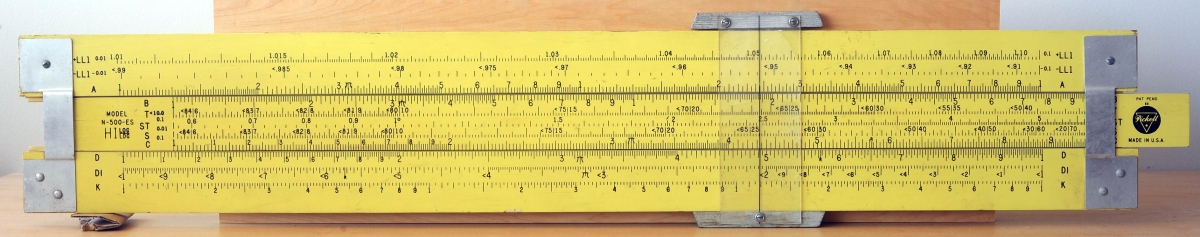

What did demonstration rules look like? They were typically between 3 and 7 feet long and made of painted or laminated wood. They might have scales on one or both sides; the selection of scales usually reflected those imprinted on one of a company’s popular classroom models. Metal braces could be used to hold the rule and its cursor together; the cursor was probably a plastic such as plexiglass. Eyes could be screwed into the rule for easier mounting on a wall.

Figure 5. A 4-foot demonstration version of Pickett’s N500-ES model copyrighted in 1962.

The “ES” in the model number refers to the company’s proprietary color “Eye-Saver Yellow”. Oughtred Society.

Most online collections of slide rules have all types of the instrument mixed together, so users must search by keyword and/or page through the whole collection—some of these are listed on the Collections page of this article. Additionally, demonstration slide rules tend to comprise a very small part of private and museum collections, so websites may have no more than two or three oversized rules designed for mounting on a wall or blackboard. Nonetheless, demonstration slide rules may be viewed in groups in a few collections.

The online International Slide Rule Museum (ISRM) offers a full page of images and descriptions, most organized by manufacturer. Some captions have links to their original web locations, and some images have links to larger versions. As was implied on the previous page of this article, ISRM offers additional images of demonstration slide rules in use on its “Photos of People with Slide Rules” page. Search on the page (e.g., with “option-F” or “command-F”) for the keywords “demonstration” or “classroom”.

The online International Slide Rule Museum (ISRM) offers a full page of images and descriptions, most organized by manufacturer. Some captions have links to their original web locations, and some images have links to larger versions. As was implied on the previous page of this article, ISRM offers additional images of demonstration slide rules in use on its “Photos of People with Slide Rules” page. Search on the page (e.g., with “option-F” or “command-F”) for the keywords “demonstration” or “classroom”.

Use the keyword “classroom” to produce a page of demonstration slide rules in the Oughtred Society’s Archive of Collections, which features items owned by members who shared images of their collections with the Society for educational purposes. Some of the rules shown are transparencies for use with an overhead projector.

Use the keyword “classroom” to produce a page of demonstration slide rules in the Oughtred Society’s Archive of Collections, which features items owned by members who shared images of their collections with the Society for educational purposes. Some of the rules shown are transparencies for use with an overhead projector.

The single demonstration slide rule in Harvard University’s Collection of Historical Instruments is easy to call up in a keyword search.

The single demonstration slide rule in Harvard University’s Collection of Historical Instruments is easy to call up in a keyword search.

The MIT Museum owns two demonstration slide rules, although only one had been photographed at the time this article was written.

The MIT Museum owns two demonstration slide rules, although only one had been photographed at the time this article was written.

Occasionally, physical examples of demonstration slide rules still turn up in storerooms of schools, universities, or businesses. More frequently, they can be found on auction sites such as eBay for a few hundred dollars. Rules designed for students tend to be more plentiful and less expensive for those inclined to seek them out; some suggestions for online collections are provided on the next page.

Keys to Mathematical Treasure Chests: Classroom Slide Rules – Rules for Student Use

Most slide rule manufacturers (and there were at least 800 of them [Keane 2008]) made products for a range of audiences:

- General-purpose rules for working professional, with scales capable of calculating arithmetic operations, logarithms, square and cube roots, exponents, trigonometric functions, and vectors.

- Special-purpose rules designed for specific occupations, such as radio engineers, meteorologists, or statisticians.

- Rules with a limited set of scales to train high school and undergraduate students, apprentices, and others in the process of masting computing techniques.

Hundreds, if not thousands, of models of slide rules were thus designated for student use between about 1890 and 1970. Companies like K&E vigorously advertised their student slide rules, highlighting especially the lower prices that were made possible by both fewer scales—which reduced a firm’s development time and the complexity of engraving—and, probably more significantly, cheaper materials such as cardboard and plastic. These less expensive rules were more consumable and less likely to survive for long periods of time, but so many millions of them were made that plenty can still be found in thrift stores or estate sales as well as in museum collections.

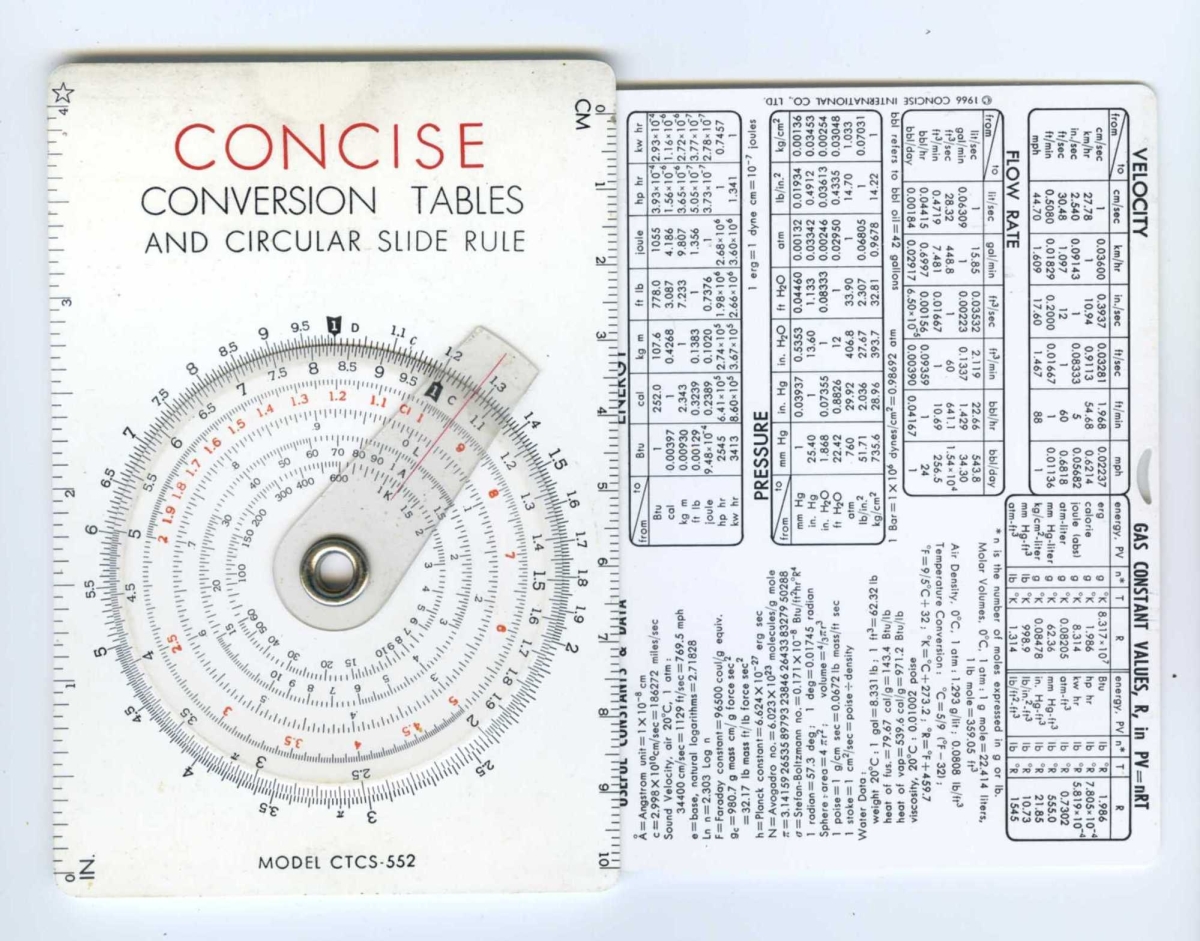

Figure 6. Although this article has focused on linear slide rules, the circular slide rule shown above was designed by students for students. It could carry out multiplication and division, determine logarithmic values, and compute squares, cubes, square roots, and cubic roots. It was distributed after 1966 by a Japanese company as model CTCS-552 under the US brand name Concise. Smithsonian Institution negative number NMAH-AHB2009q09077.

Even though student slide rules were far more ubiquitous than demonstration slide rules, most searches on the keywords “student slide rules” again yield few results. A search on the phrase “student slide rule” using the link at the top of the home page for the International Slide Rule Museum brings up 72 objects to explore. The Oughtred Society’s Archive of Collections also comes through with a number of examples. Some other options:

Even though student slide rules were far more ubiquitous than demonstration slide rules, most searches on the keywords “student slide rules” again yield few results. A search on the phrase “student slide rule” using the link at the top of the home page for the International Slide Rule Museum brings up 72 objects to explore. The Oughtred Society’s Archive of Collections also comes through with a number of examples. Some other options:

- The Smithsonian’s Collections Search Center returns two rules and three sets of instructions, which could be used to supply manufacturers and models for additional searches.

- Harvard University’s Collection of Historical Scientific Instruments displays two objects.

- Two objects from the Computer History Center may be viewed.

- The MIT Museum has two objects so labeled, although only one has been photographed.

- The Science Museum Group provides 5 records, but only one contains an image.

One way to do further research is to collect model numbers for one or more manufacturers or retailers and then search the internet for those model numbers. Clark McCoy’s scanned pages from K&E Catalogs and Price Lists offer an excellent starting point; K&E’s occasional Educational Products Catalogs are especially helpful.

One way to do further research is to collect model numbers for one or more manufacturers or retailers and then search the internet for those model numbers. Clark McCoy’s scanned pages from K&E Catalogs and Price Lists offer an excellent starting point; K&E’s occasional Educational Products Catalogs are especially helpful.

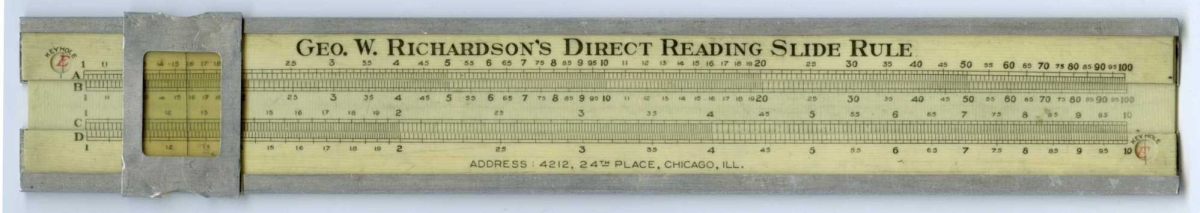

Figure 7. Richardson Direct Reading Slide Rule, ca 1909. George Washington Richardson (ca 1866–1940) was an individual American maker who tried to make inexpensive, basic slide rules that were affordable for students and blue-collar workers. Smithsonian Institution negative number NMAH-AHB2009q09170.

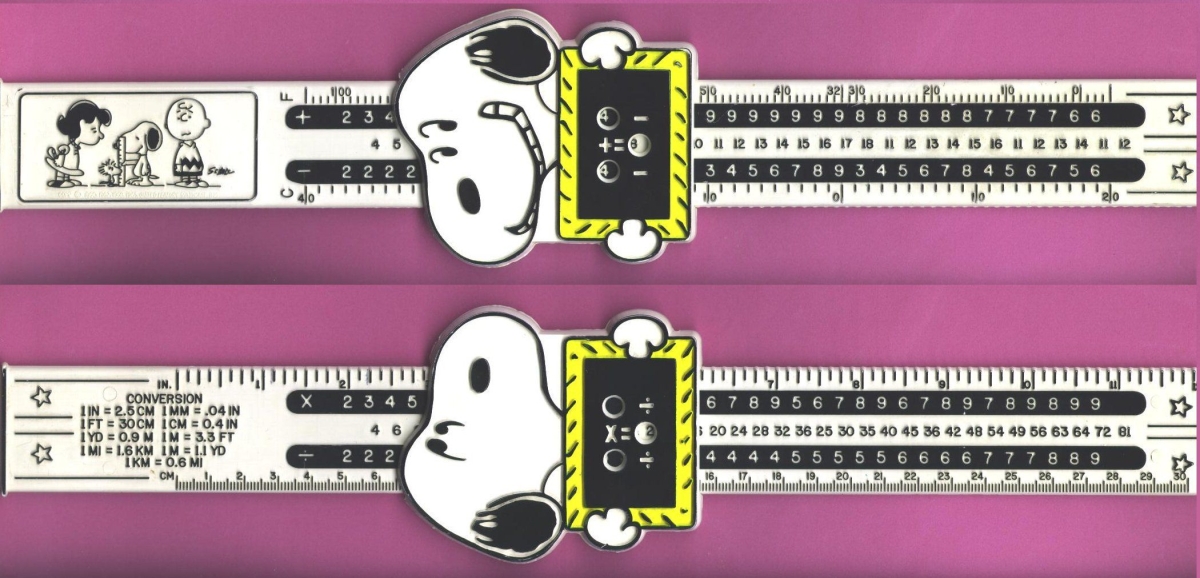

Early in the 20th century, American college professors and administrators made a concerted effort to outsource instruction in the slide rule to high schools, so that freshmen could move directly into the technical work of mathematics, engineering, and physics [Kidwell, Ackerberg-Hastings, and Roberts 2008, pp. 117–122]. Indeed, as late as the 1970s, popular cartoons were licensed to intrigue small children with the possibility of STEM careers—my parents gave me one of the Snoopy “slide rules” shown in Figure 8 when I was in elementary school. Today, both secondary schoolteachers and undergraduate professors provide enrichment activities based on slide rules. The instruments make excellent manipulatives for math circles, too. Some links to help readers get started can be found on the next page.

Figure 8. Snoopy Slide Rule, 1960s–1970s. International Slide Rule Museum.

Keys to Mathematical Treasure Chests: Classroom Slide Rules – Resources for Today’s Classrooms

Almost since slide rules disappeared from professional use, educators have considered ways to bring them back into mathematics classrooms. As with historical slide rules for student use, I have made no effort at a comprehensive listing of the resources available to instructors who are interested in how slide rules might “engage students in the visual experience of problem-solving, illustrate the connections between mathematics and real-life problems, and increase students’ appreciation for history” [Ackerberg-Hastings and Shell-Gellasch 2014, p. 9].

Introductory Overviews

The Reference Manual offered by the Oughtred Society may be the best single source for finding out what a slide rule is and does and learning about some of the major manufacturers [Davis and Hume 2012]. Just read carefully; by page 99 you may be tempted to become a collector yourself!

An illustrated self-guided course with 28 (brief) lessons and a link to an emulator is also available from the home page of the International Slide Rule Museum. Eric Marcotte’s chart of common scales was helpful to me when I was cataloguing the National Museum of American History’s over 200 slide rules.

How to Use a Slide Rule

If you or your students want to get started with slide rules more quickly than reading through a manual, short lessons that come up on search engines include a 1-pager by Liyen Liang of MIT and high school teacher Jay Ballauer’s Slide Rule Basics.

Do your students respond to videos? A training film from 1957 is available from the 16mm Educational Films channel on YouTube. More recently, a Professor Herning has recorded 65 videos on the general techniques of use and various specialized slide rules. Auto-generated closed captions and transcripts are available from both channels.

Online Emulators

The International Slide Rule Museum operates a free loaner program for instructors who are able to plan slide rule experiences in advance. Numerous virtual slide rules are available for immediate gratification, including 7 emulators at Derek’s Virtual Slide Rule Gallery and a collection of 43 replicas with downloadable code posted by Robert P. Wolf.

How to Make a Slide Rule

Printable templates for scales abound on the internet; several can be accessed through the International Slide Rule Museum’s Slide Rule Scales page or the General Information section of the Oughtred Society’s Links Library. In keeping with the spirit of this Mathematical Treasure Chest, Earl C. Rex explained in 1940 how to build a demonstration slide rule from lengths of baseboard [Rex 1940]. This article is available if your institution subscribes to the Wiley Online Library.

Classroom Use of Slide Rules

What might an instructor actually do with a class full of students and slide rules? In 2005 Paul R. Huff and Dagmar Rutzen both offered reports with teaching suggestions to the Journal of the Oughtred Society [Huff 2005; Rutzen 2005]. At a 2017 conference for earth educators, Victor Ricchezza of Georgia State University outlined a lab activity that uses slide rules to motivate skills for reading graphs, such as distinguishing between types of scales. He also provided files for 3D-printing slide rule bases. Richard Blake of STEMpunk offers an in-person and livestreamed presentation on “When Slide Rules Ruled,” but he has made many of the supporting materials available for free so others can use his efforts as a role model.

Keys to Mathematical Treasure Chests: Classroom Slide Rules – Conclusion, References, About the Author

Conclusion

Although organizations of slide rule collectors are justifiably worried about the aging of their membership, interest in the devices remains high and the history and use of slide rules is incredibly well-documented on the internet. This article has aimed to narrow down the resources instructors might consult by focusing on the slide rules 20th-century students would have actually encountered in high school or college classrooms: the oversized demonstration slide rule, suitable for mounting on a wall or blackboard and visible to an entire classroom at once, and the student slide rule, a label that encompasses the many models manufactured for instructional use by individuals. Today’s instructors can share images from the museum collections highlighted in this article, and they can consider implementing the activities described on the Resources page. Happy slipsticking!

References

Ackerberg-Hastings, Amy. 2012. Slide Rules as Computers and on Computers. In Proceedings of the Canadian Society for History and Philosophy of Mathematics, edited by Tom Archibald, 12–23. Vol. 25, 38th Annual Meeting. Available by request from the author.

Ackerberg-Hastings, Amy, and Amy Shell-Gellasch. 2014, December. Online Museum Collections in the Mathematics Classroom. Convergence 11.

Cajori, Florian. 1909. A History of the Logarithmic Slide Rule and Allied Instruments. New York: The Engineering News Publishing Company.

Davis, Richard, and Ted Hume. 2012. Oughtred Society Slide Rule Reference Manual (aka All About Slide Rules). Roseville, CA: The Oughtred Society.

Huff, Paul R. 2005. Slide Rules in the Classroom—An Anecdotal Report. Journal of the Oughtred Society 14(1): 12–13.

Keane, Maribeth. 2008, November 12. Calculating the Quality of Vintage Slide Rules (interview with Mike Konshak, webmaster of the International Slide Rule Museum). Collectors Weekly.

Keuffel & Esser Co. 1924, August. Shop calculations made easy. Industrial Arts Magazine 13(8): 27A.

Keuffel & Esser Co. 1933. Drawing Instruments and Materials for High Schools, Preparatory Schools and Manual Training Schools. New York.

Kidwell, Peggy Aldrich. 2017, February 9. A curator goes to the movies: The stuff of “Hidden Figures”. O Say Can You See? Stories from the Museum. National Museum of American History.

Kidwell, Peggy Aldrich, and Amy Ackerberg-Hastings. 2014. Slide Rules on Display in the United States, 1840–2010. In Scientific Instruments on Display, edited by Silke Ackermann, Richard L. Kremer, and Mara Miniati,159–172. Scientific Instruments and Collections, vol. 4. Leyden: Brill.

Kidwell, Peggy Aldrich, Amy Ackerberg-Hastings, and David Lindsay Roberts. 2008. Tools of American Mathematics Teaching 1800–2000. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Mannheim, Amédée. 1853. Règle à calculs modifée. Nouvelles annales de mathématiques 12: 327–329.

McCoy, Clark. n.d. K&E Catalogs and Price Lists for Slide Rules.

Otnes, Robert K., ed. 1993. The Keuffel & Esser Issue. Journal of the Oughtred Society 2(1): 4–49.

Rex, Earl C. 1940. Construction of a Demonstration Slide Rule. School Science and Mathematics 40(2): 161–164.

Rudowski, Werner H. 2006. How Well Known Were Slide Rules in Germany, Austria and Switzerland Before the Second Half of the 19th Century? Journal of the Oughtred Society 15(2): 42–49.

Rutzen, Dagmar. 2005. Getting Hooked on Slide Rules—A Classroom Tale. Journal of the Oughtred Society 14(1): 14–15.

State College of Washington. 1906. Fifteenth Annual Catalogue of the State College of Washington. Olympia, WA: C. W. Gorham.

Collections

Collections Search Center, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC

History of Science Museum, University of Oxford, England

International Slide Rule Museum

K&E Company Collection and Richard (Dick) Rose Collection, MIT Museum, Cambridge, MA

Musée des Arts et Métiers, Paris, France

Science Museum Group, London, England

Searchable Galleries, Oughtred Society

Slide Rules, The Museum of HP Calculators, curated by David G. Hicks

Slide Rules, Whipple Museum of the History of Science, University of Cambridge, England

Slide Rules Object Group, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC

The Slide Rule Universe, Sphere Research Corporation, West Kelowna, British Columbia

University of Toronto Scientific Instruments Collection, Toronto, Ontario

Acknowledgements

I thank Peggy Aldrich Kidwell for the concept of this series and for suggestions on the draft of this article.

About the Author

Amy Ackerberg-Hastings prepared web descriptions for the slide rules in the mathematics collections of the National Museum of American History between 2011 and 2013 as part of work funded by Ed and Diane Straker. She has written numerous articles about the history of mathematical instruments and is currently co-editor of Convergence.