Algebra Tiles Explorations of al-Khwārizmī’s Equation Types

This article offers an interactive method of visualizing the algebraic solution methods presented by Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwārizmī (780–850 CE) in his highly influential text Al-Kitab almukhtasarfi hisab al-jabr wa’l-muqabala (Compendium on Calculating by Completion and Reduction). Using algebra tile manipulatives in as much accordance as possible with al-Khwārizmī's completely verbal descriptions of those methods, the multi-representational module explores all six of his equation types: squares = roots; squares = numbers; roots = numbers; roots and squares = numbers; squares and numbers = roots; roots and numbers = squares. Originally developed for use in a history of mathematics course, the audience may include students from a diversity of backgrounds and levels, including preservice and practicing secondary mathematics teachers, as well as high school students. Certain parts of the activity could also be used with preservice and practicing elementary mathematics teachers. Unlike other activities that prompt these various audiences to explore al-Khwārizmī's algebraic procedures via modern symbolic representations (e.g., [Otero 2019]), the activity proposed in this article offers a new perspective by providing students with a concrete way to visualize those procedures geometrically.

This article begins with an overview of al-Khwārizmī’s Compendium on Calculating by Completion and Reduction, before introducing the basic use of algebra tiles to represent the quantities he used in that treatise. The next two sections of the article then present and discuss examples of how to model al-Khwārizmī’s two types of equations (simple and compound). For instructors who wish to go into more depth with their students, a section that illustrates how algebra tiles could be used to model al-Khwārizmī’s procedures for calculating by completion and reduction in more complicated problems is also included. The article closes with some suggestions and advice for classroom implementation.

Figure 1. A page from al-Khwārizmī's algebra text that corresponds to page 15 of the classic

19th-century translation into English by Friedrich August Rosen (1805–1837) [Rosen 1831].

Image retrieved from Convergence’s Mathematical Treasures collection.

Algebra Tiles Explorations of al-Khwārizmī’s Equation Types: al-Khwārizmī’s Compendium on Calculating by Completion and Reduction

Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwārizmī (780–850 CE) was the first mathematician to write an algebra book: Al-Kitab almukhtasar fi hisab al-jabr wa’l-muqabala (Compendium on Calculating by Completion and Reduction1). In this treatise, al-Khwārizmī first emphasized the notion of number via his statements [Rosen 1831, 5]:

When I considered what people generally want in calculating, I found that it always is a number.

I also observed that every number is composed of units, and that any number may be divided into units.

Moreover, I found that every number, which may be expressed from one to ten, surpasses the preceding by one unit: afterwards the ten is doubled or tripled, just as before the units were: thus arise twenty, thirty, etc., until a hundred; then the hundred is doubled and tripled in the same manner as the units and the tens, up to a thousand; then the thousand can be thus repeated at any complex number; and so forth to the utmost limit of numeration.

He then proposed a classification of numbers into three types [Rosen 1831, 5–6]:

I observed that the numbers which are required in calculating by Completion and Reduction are of three kinds, namely, roots, squares, and simple numbers relative to neither root nor square.

A root is any quantity which is to be multiplied by itself, consisting of units, or numbers ascending, or fractions descending.

A square is the whole amount of the root multiplied by itself.

A simple number is any number which may be pronounced without reference to root or square.

Here, the phrase “in calculating by Completion and Reduction” is a reference to the practice of equation-solving. This, together with al-Khwarizi’s descriptions of the kinds of numbers he had observed in that practice, suggests a natural correspondence between his categories and the three terms we associate with quadratic equations today: “roots” with the linear term; “squares” with the quadratic term; and “simple numbers” with the constant term.

We also notice the quantitative aspect of al-Khwārizmī’s roots, squares, and simple numbers categories, which allows any two of the three to be used to generate a simple equation [Rosen 1831, 8]:

A number belonging to one of these three classes may be equal to a number of another class ; you may say, for instance, “squares are equal to roots," or “squares are equal to numbers,” or “roots are equal to numbers."

We further see the emergence of a new kind of quantity, which al-Khwārizmi used to describe three “compound species” equations [Rosen 1831, 8]:

I found that these three kinds; namely, roots, squares, and numbers, may be combined together, and thus three compound species arise; that is, “squares and roots equal to numbers;” “squares and numbers equal to roots;” “roots and numbers equal to squares.”

al-Khwārizmī’s treatise is thus generally considered a handbook for solving linear and quadratic equations. His text classified these, however, as six different equation types. The following table outlines this classification, along with the examples of each type that al-Khwārizmī solved in the first part of his text. Note that the word “dirhem” that appears in the example for Type 4 refers to a type of coin that was historically used in Baghdad; it was often used by al-Khwārizmī as the units for the simple number in an equation.

|

Equation Type (prose format) |

Equation Type |

|

Type 1. Squares are equal to roots

|

\[ax^2 = bx\] |

|

Type 2. Squares are equal to numbers

|

\[ax^2 = c\] |

|

Type 3. Roots are equal to number

|

\[bx = c\] |

|

Type 4. Roots and squares are equal to numbers

|

\[bx+ax^2 = c\] |

|

Type 5. Squares and numbers are equal to roots

|

\[ax^2+c = bx\] |

|

Type 6. Roots and numbers are equal to squares

|

\[bx+c = ax^2\] |

Notes

1. Al-jabr = completion; al-muqabala = reduction.

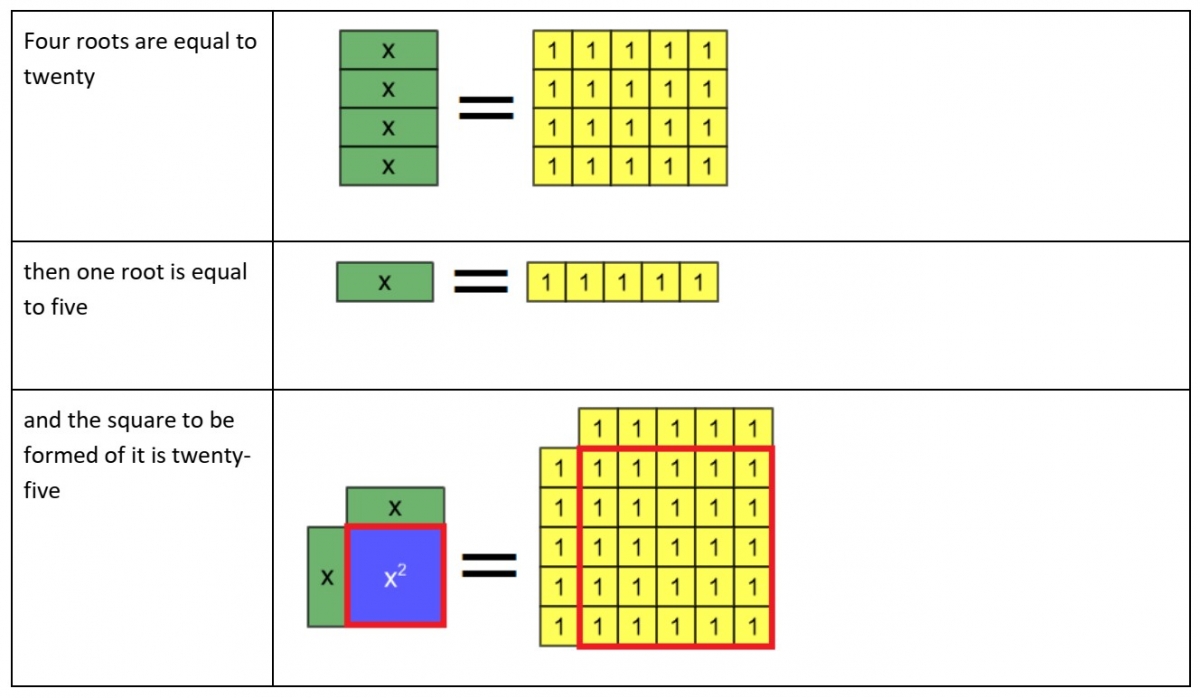

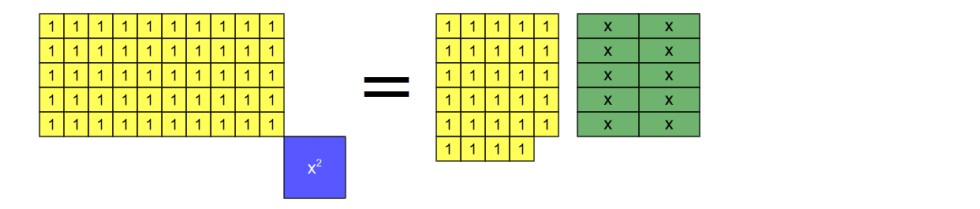

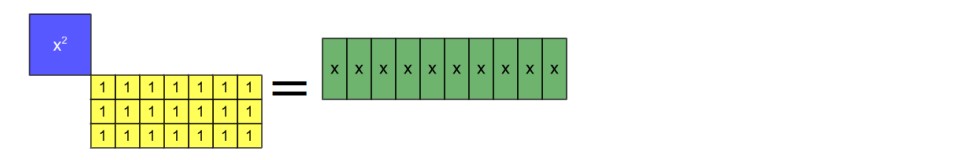

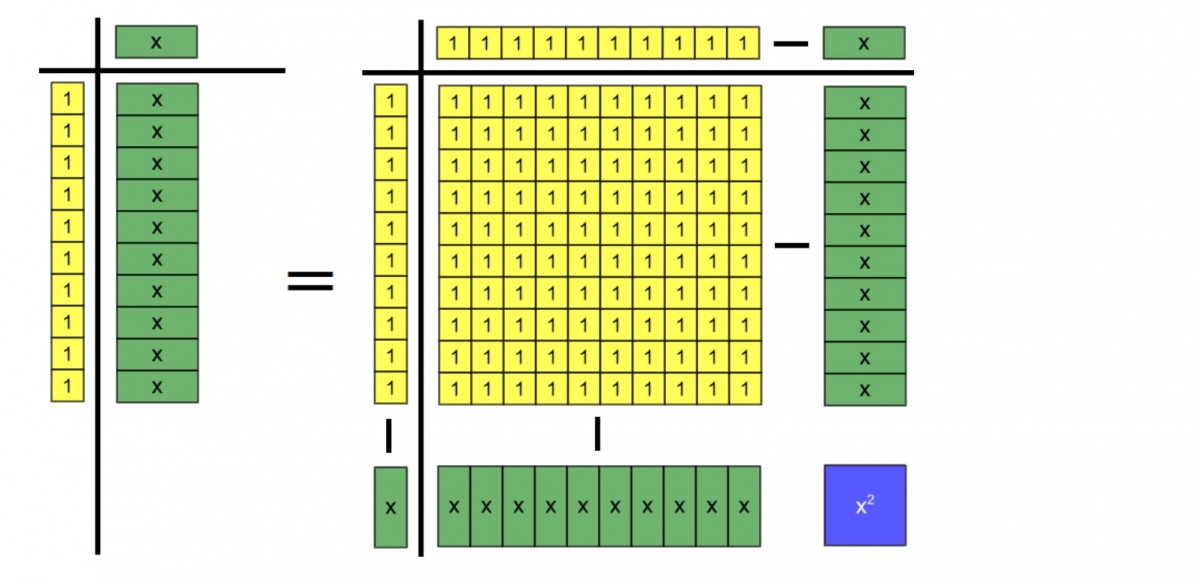

Algebra Tiles Explorations of al-Khwārizmī’s Equation Types: Representing al-Khwārizmī’s Quantities with Algebra Tiles

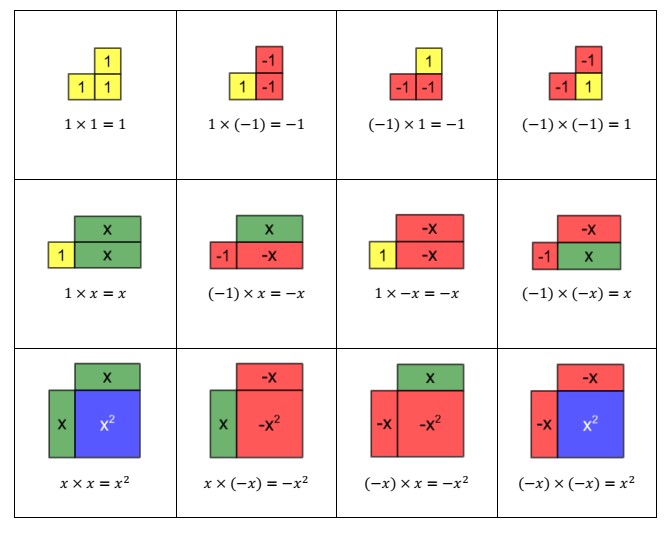

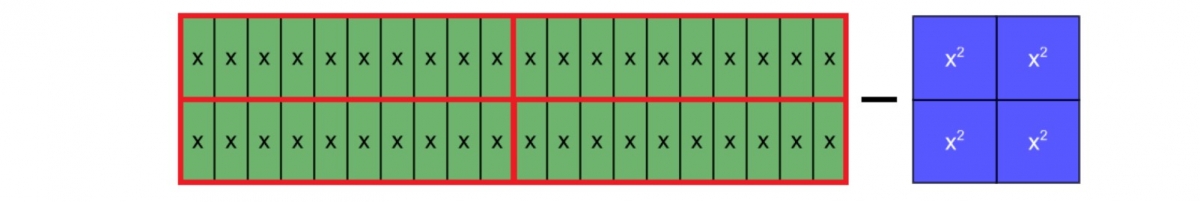

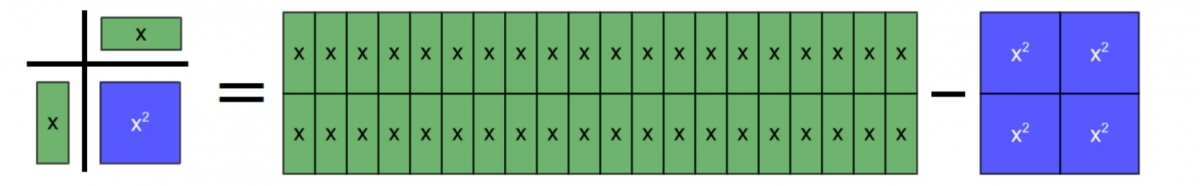

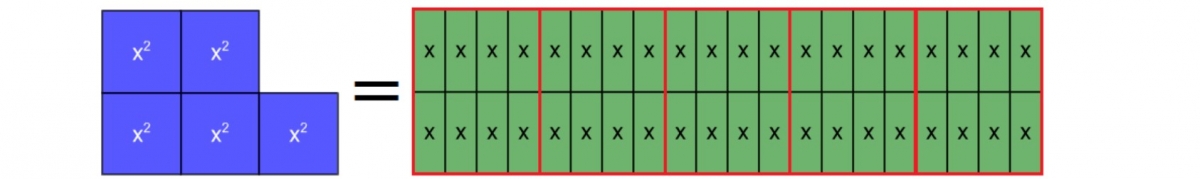

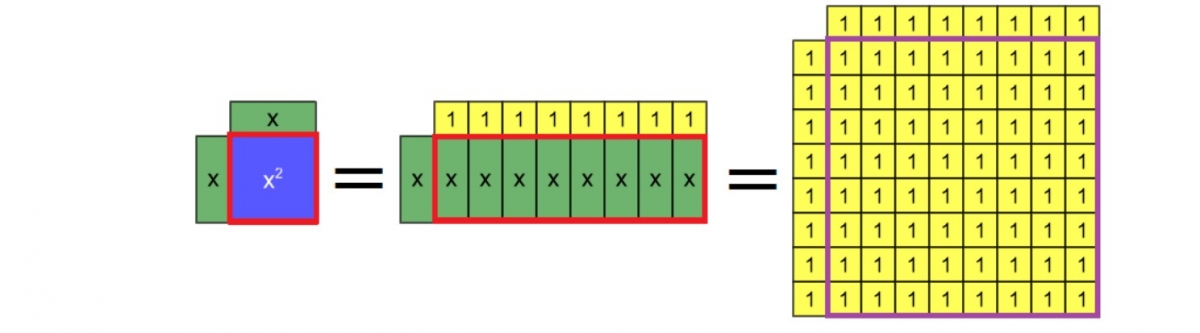

Since a quantitative approach is prevalent in al-Khwārizmī’s text, in order to set up the historically based portion of the activity, I first introduced algebra tiles to my students in a manner which shows how the basic quantities involved in today’s quadratic equations can be represented as products. For that purpose, each quantity is derived using a multiplication mat by placing the two dimension tiles (one on top and the other on left) respectively:2

Note that negative quantities are included in the algebra tile representations. In the Al-Kitab almukhtasar fi hisab al-jabr wa’l-muqabala, however, al-Khwārizmī used only positive integers and fractions as the coefficients and solutions of equations. The system of numbers used by al-Khwārizmī was thus different from the one that is used in present-day classrooms. Interestingly, however, al-Khwārizmī did provide rules for multiplying negatives [Rosen 1831, 25–26]:

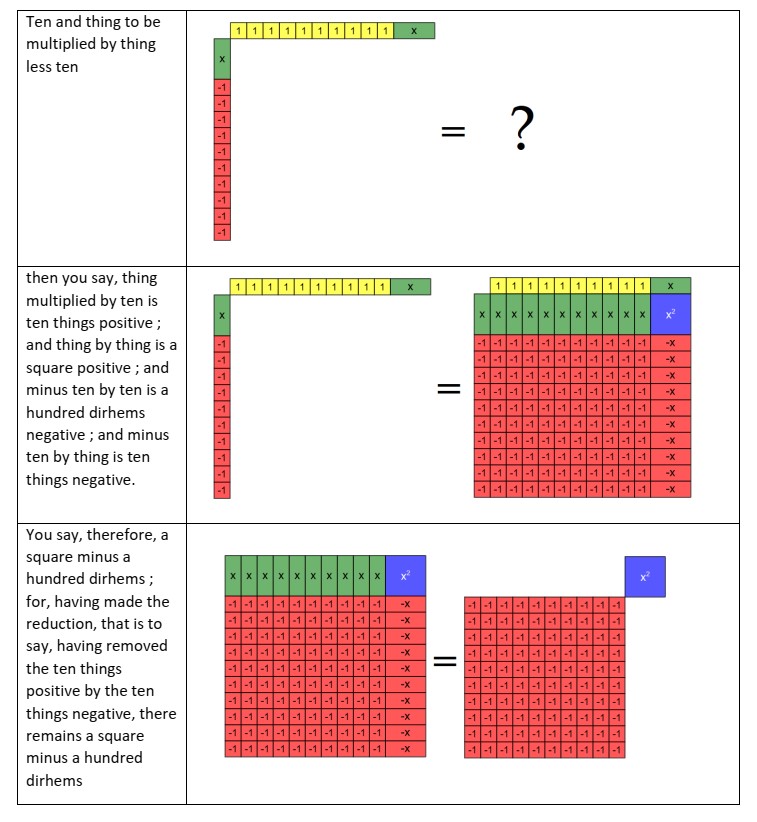

If the instance be, “ten and thing to be multiplied by thing less ten, then you say, thing multiplied by ten is ten things positive; and thing by thing is a square positive; and minus ten by ten is a hundred dirhems negative; and minus ten by thing is ten things negative. You say, therefore, a square minus a hundred dirhems; for, having made the reduction, that is to say, having removed the ten things positive by the ten things negative, there remains a square minus a hundred dirhems.

The following table illustrates how the computation in this excerpt might be modeled using algebra tiles to represent the negative quantities:

An interesting observation to discuss with students is how the so-called “zero principle” manifests itself as the appearance of the zero pairs “the ten things positive” and “the ten things negative.” Another interesting point to observe is the relevance to the well-known “difference of squares” identity \((A+B)(A-B) = A^2 - B^2\) to this computation and how algebra tiles involving negative quantities can be used to represent and reinforce it.

Notes

2. These figures were generated using the online algebra tiles applet mathies.ca/learningTools.php.

Algebra Tiles Explorations of al-Khwārizmī ’s Equation Types: Modeling the Simple Equations

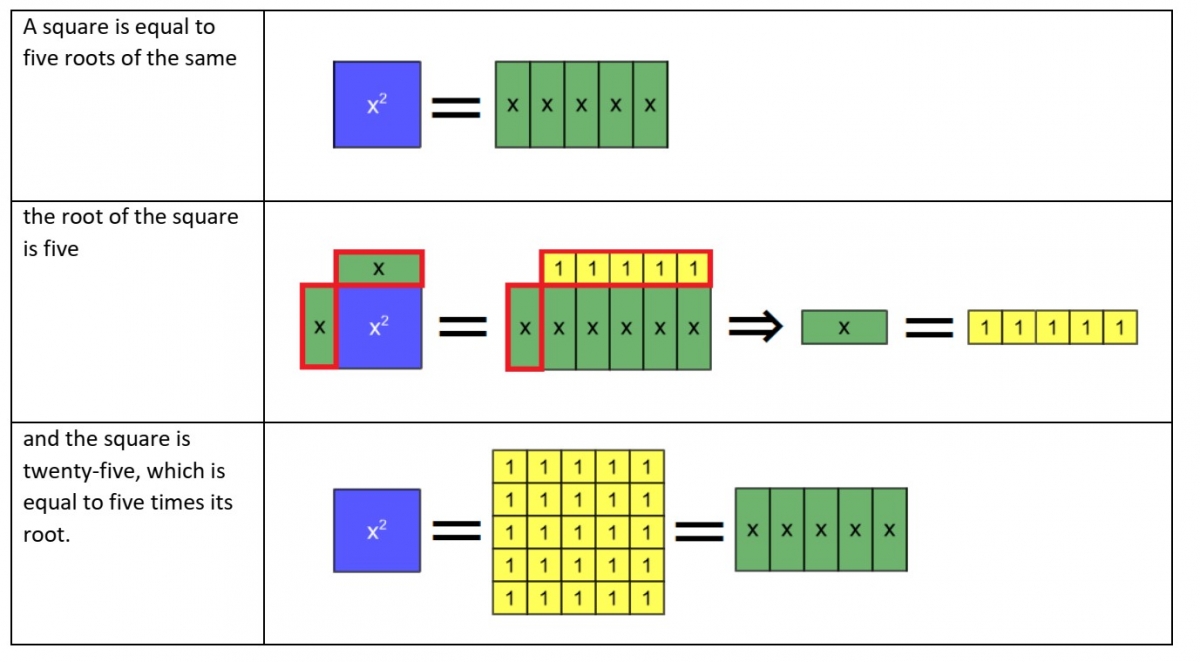

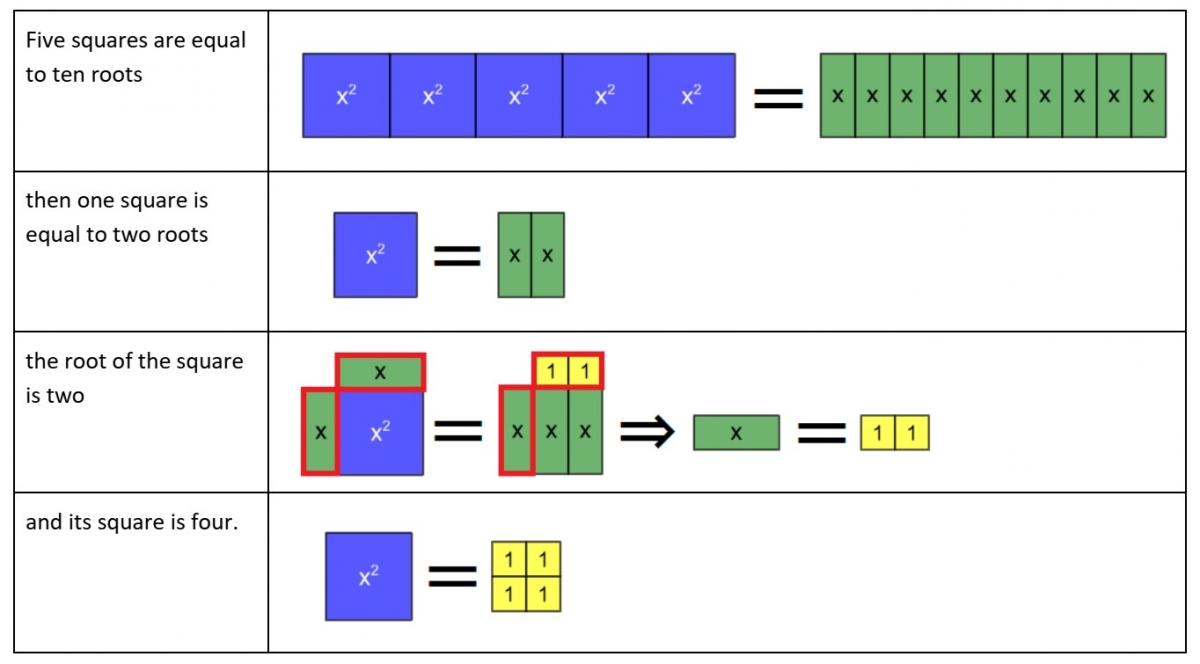

This section shows how the rules used by al-Khwārizmī to solve his three basic types of equations (squares = roots; squares = numbers; roots = numbers) can be simulated using algebra tiles. al-Khwārizmī presented these examples verbally in prose format. The examples in this section constitute the basis for modeling all six equations using algebra tiles in that they illustrate the essence of how to physically represent al-Khwārizmī’s prose expressions. In what follows, all descriptions are taken from [Rosen 1831, 6–7).

Example 1: Squares are Equal to Roots (Type 1)

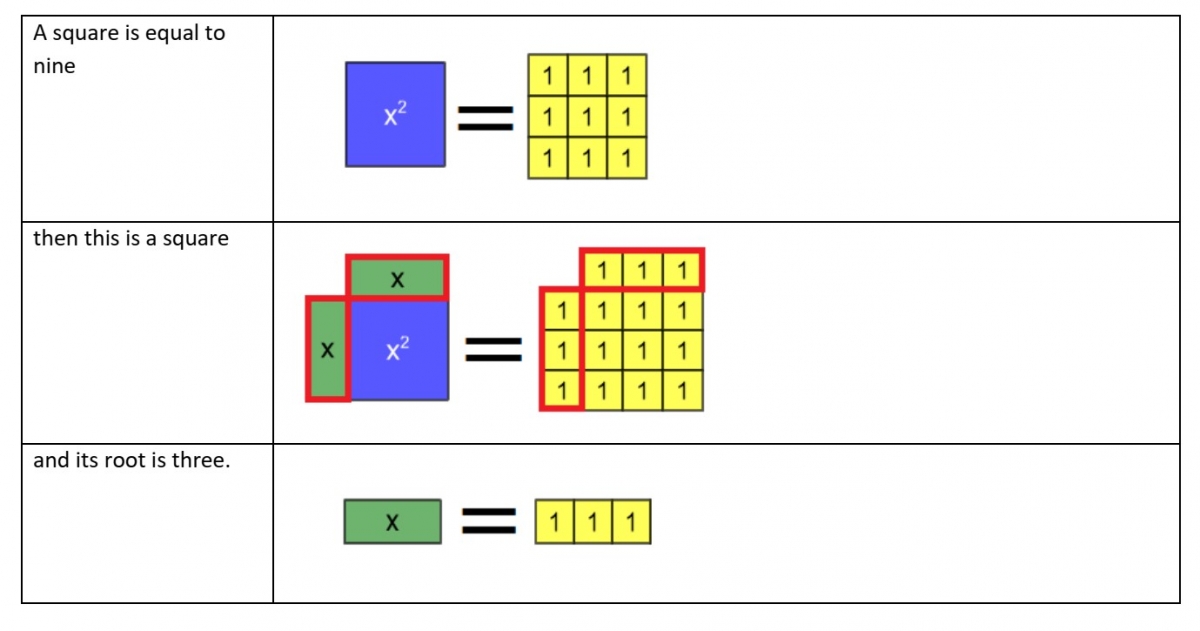

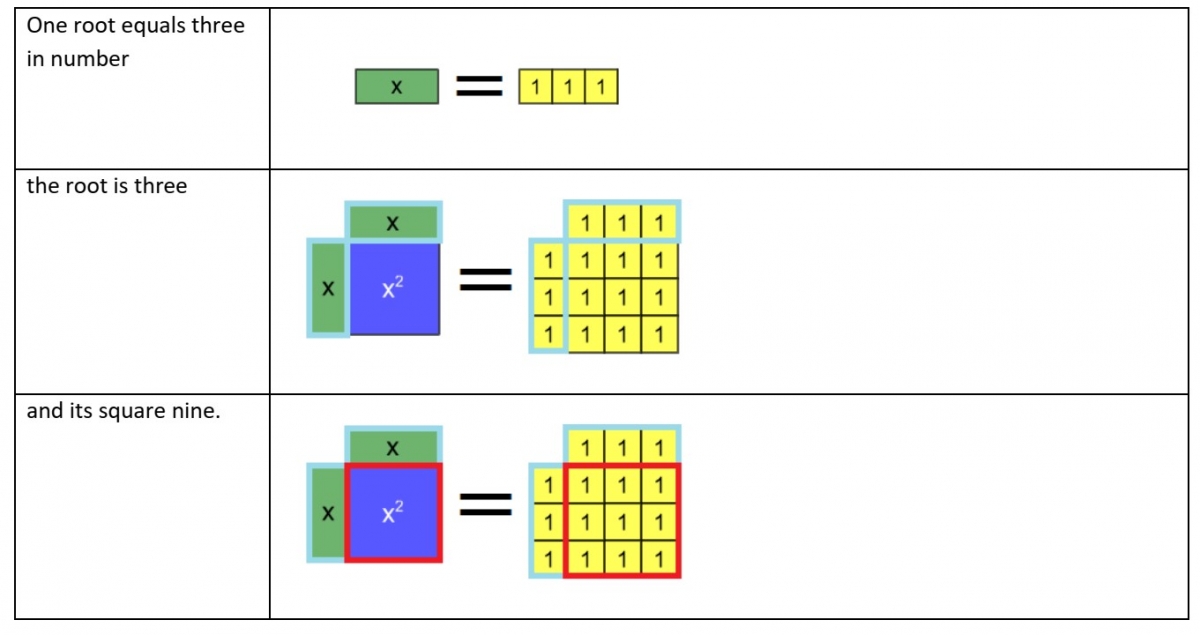

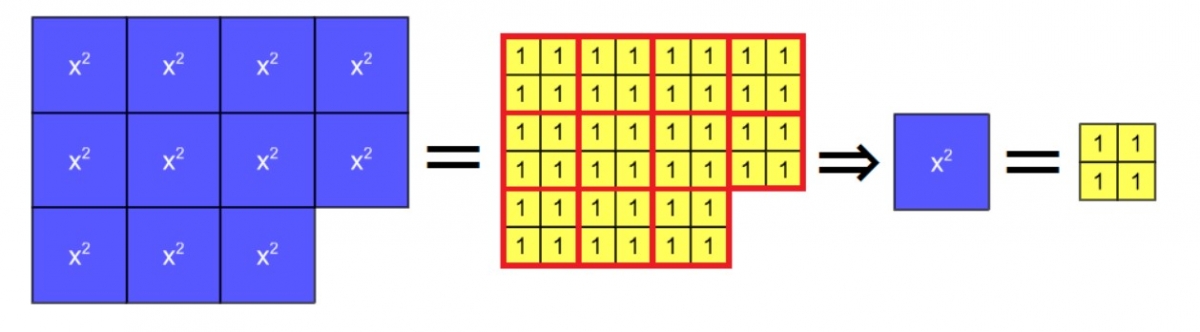

Example 2: Squares are Equal to Numbers (Type 2)

Example 3: Roots are Equal to Numbers (Type 3)

Students may find it interesting that al-Khwārizmī always stated the value of the square, as well as the root, in his examples. This is the case even in Example 3, where the value of the root (x=3) is given in the problem statement.

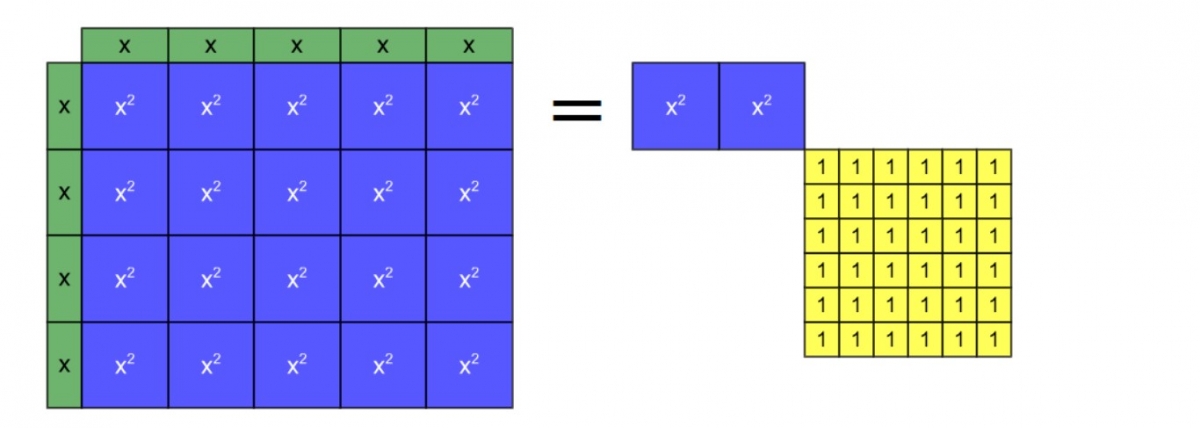

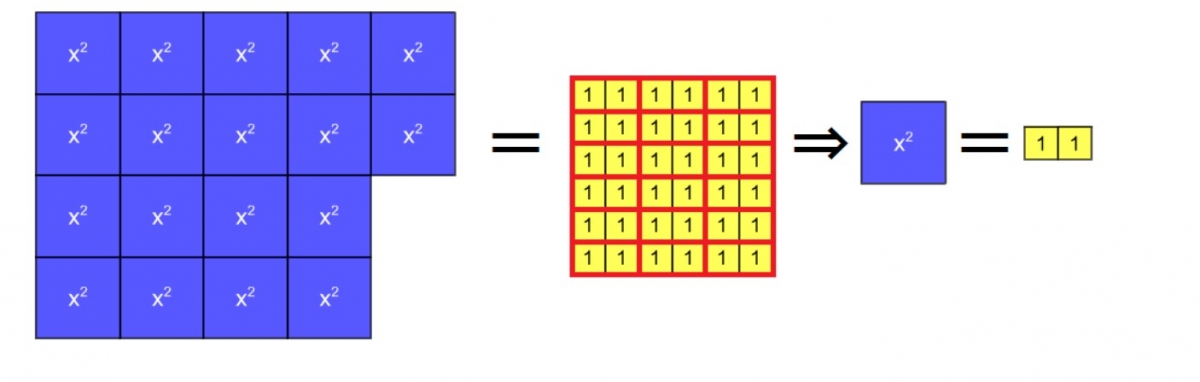

The three examples above are all associated with monic polynomials. The next two examples illustrate al-Khwārizmī’s procedures for obtaining one entire square “whenever you meet with a multiple or sub-multiple of a square” [Rosen 1831, 13]; that is, the procedure for obtaining a leading coefficient of 1 in a non-monic quadratic equation. As shown in these examples, the squares, roots, and numbers are simultaneously scaled by the same ratio where that ratio is chosen in order to obtain a single square. A similar procedure was used with linear equations (roots = numbers), as is shown in Example 6. While it is relatively straightforward to model this procedure with algebra tiles in the case of multiple squares or roots (Examples 4 and 6), the lack of fractional tiles makes the case of submultiples more complicated to set up (Example 5). In fact, some of al-Khwārizmī’s equations involve fractions in ways that are impossible to represent with algebra tiles, as we describe in our discussion of Example 10 in a later section.

Example 4: Squares are Equal to Roots (Type 1), beginning with a multiple of a square

Example 5: Squares are Equal to Numbers (Type 2), beginning with a submultiple of a square

Example 6: Roots are Equal to Numbers (Type 3) , beginning with a multiple of the root

Algebra Tiles Explorations of al-Khwārizmī's Equation Types: Modeling the Compound Equations and the Moiety Principle

This section focuses on modeling the three compound species in al-Khwārizmī’s algebra text using a step-by-step problem-solving approach, with each case treated in a separate subsection:

- Type 4: roots and squares = numbers

- Type 5: squares and numbers = roots

- Type 6: squares = roots and numbers

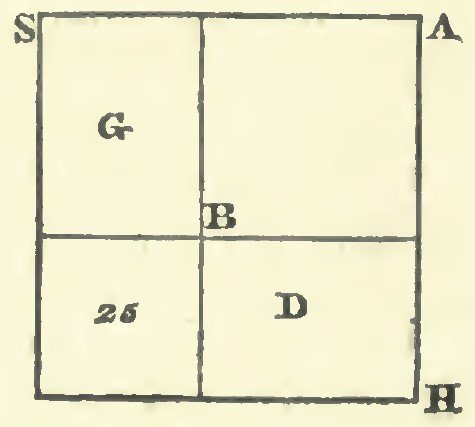

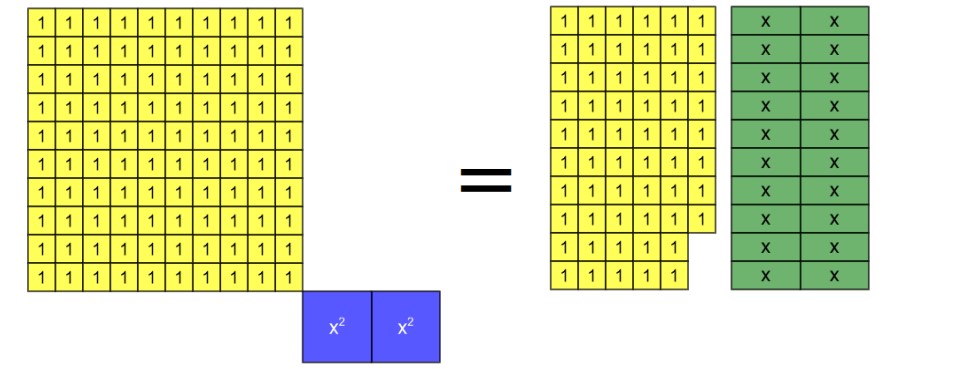

As al-Khwārizmī noted, the three basic equations (Types 1-2-3) discussed in the previous section “do not require that the roots be halved” [Rosen 1831, 13]. In the latter three (Types 4-5-6), on the other hand, he asserted that “halving the roots is necessary” [Rosen 1831, 13]. The utilization of moities is thus also a key feature in modeling the solutions of equations of Types 4-5-6 using algebra tiles representations. He also provided geometric constructions (based on specific equation examples) for each of these three equation types “to point out the reasons for halving” [Rosen 1831, 13]. For equations of Types 5 and 6, the diagrams that accompany these synthetic constructions are not transferrable to an algebra tile representation. As indicated by Figure 2, however, the second diagram that al-Khwārizmī gave in his demonstration for Type 4 equations (based on the example \(x^2+10x = 39\)) is reminiscent of the algebra tile models we provide in this section. Notice in particular the small square of area 25 in the lower left-hand corner, which represents the final step in the "Completing the Square" technique for solving this equation. In fact, similar diagrams are widely used with an equation of Type 4 to illustrate that solution technique.

Figure 2. Second diagram in al-Khwarizmi's geometric demonstration of Type 4

using the equation “a Square and twenty-one Dirhems are equal to ten Roots” [Rosen 1831, 16].

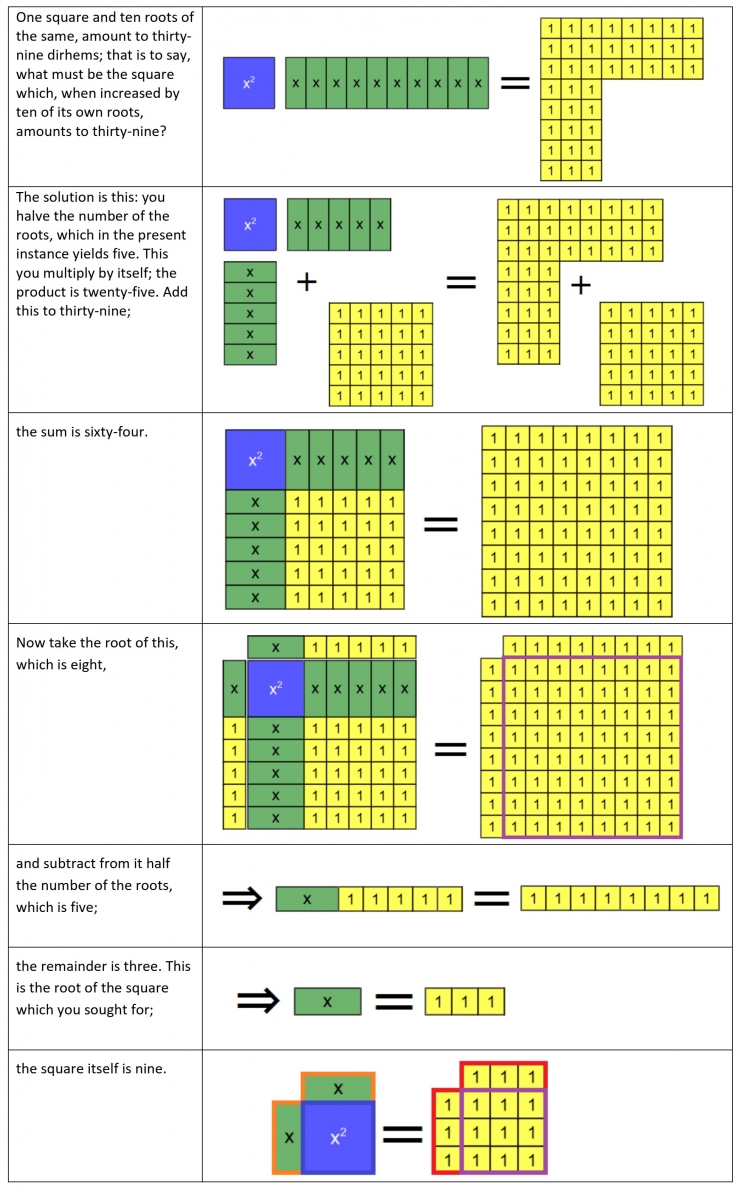

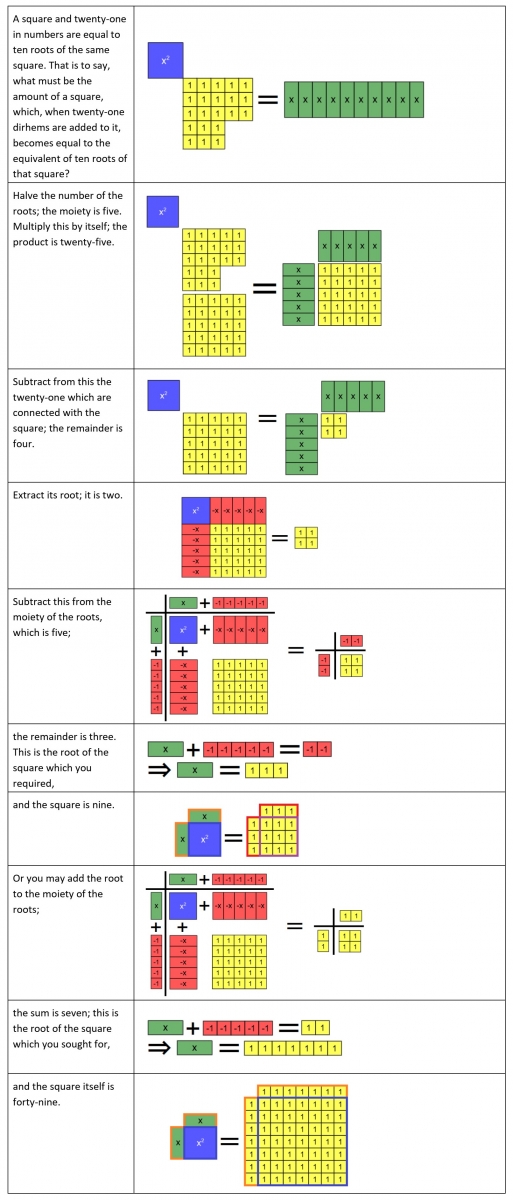

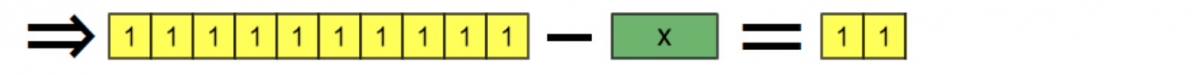

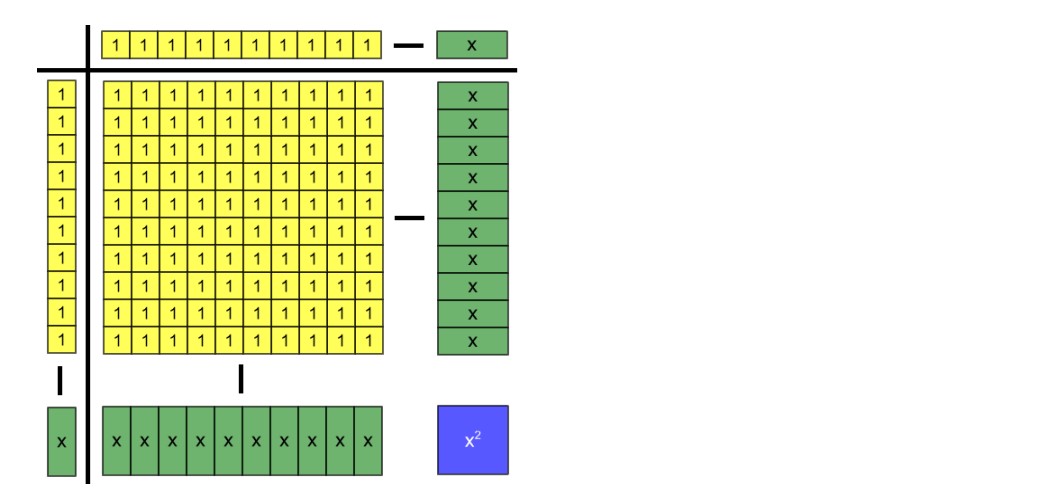

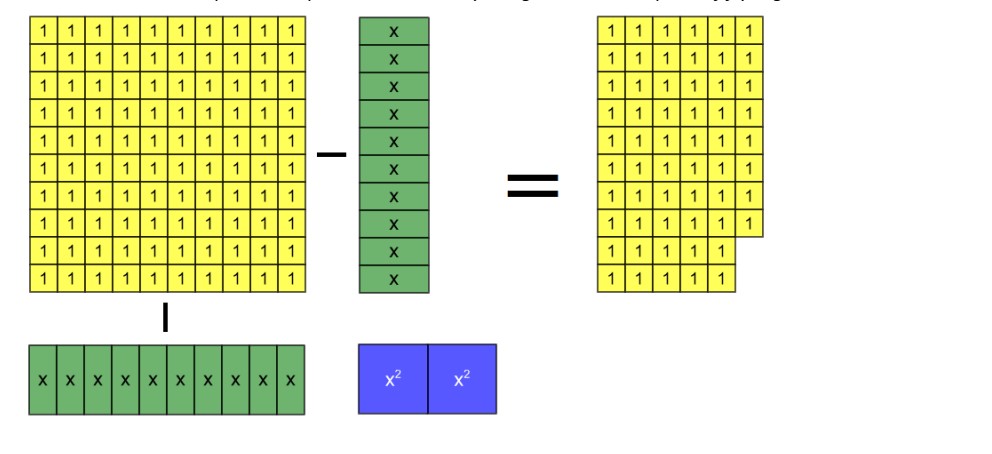

Algebra Tiles Explorations of al-Khwārizmī ’s Equation Types: Roots and Squares are Equal to Numbers

In our example for this case (taken from [Rosen 1831, 8]), we first model al-Khwārizmī’s procedure for producing the positive root of the given quadratic. We then illustrate how the use of algebra tiles suggests a modification of that procedure that produces the negative root. Here and in our other examples of compound species, it is important for students to be aware that whenever al-Khwārizmī added a quantity associated with one side of an equation (e.g., the second step of Example 7a), it is implied by the algebra tile representation that the same quantity is added to the other side as well. A classroom discussion of why this is necessary in the algebra tile representation, and also why it is not needed in al-Khwārizmī’s verbal description of his procedure, could be fruitful with prospective teachers.

Example 7a: Roots and Squares are Equal to Numbers (Type 4), positive solution

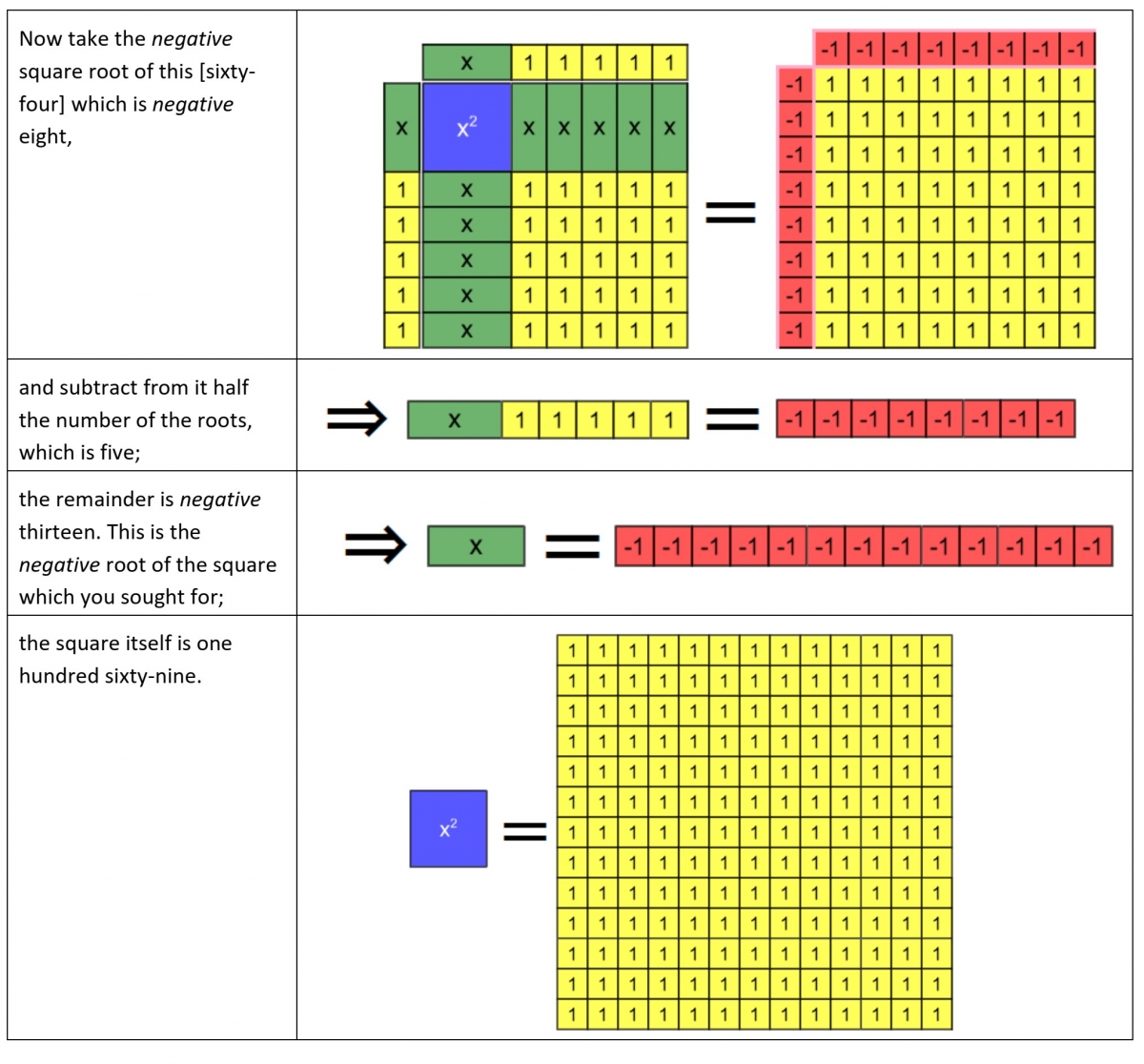

The procedure for obtaining the negative solution was not discussed in al-Khwārizmī’s solution, due to the restrictions in his number system that were mentioned in the last section. Below, we show a procedure for obtaining the negative solution by involving negative tiles to represent the extraction of a negative square root.

Example 7b: Roots and Squares are Equal to Numbers (Type 4), negative solution

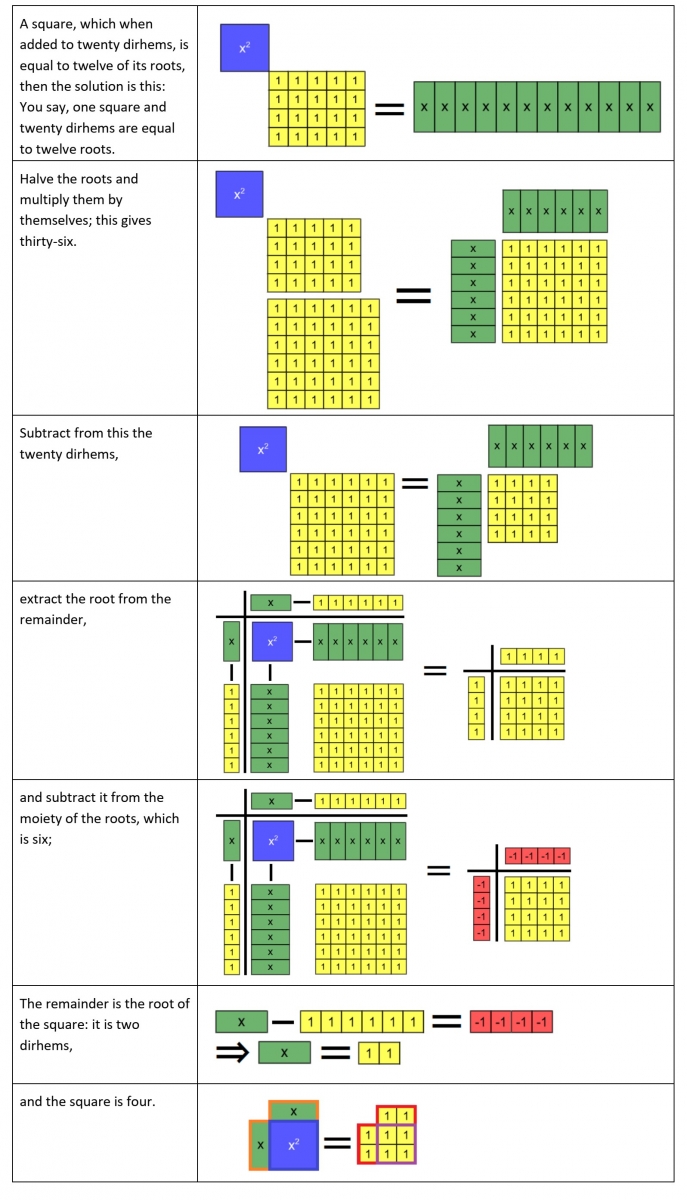

Algebra Tiles Explorations of al-Khwārizmī ’s Equation Types: Squares and Numbers are Equal to Roots

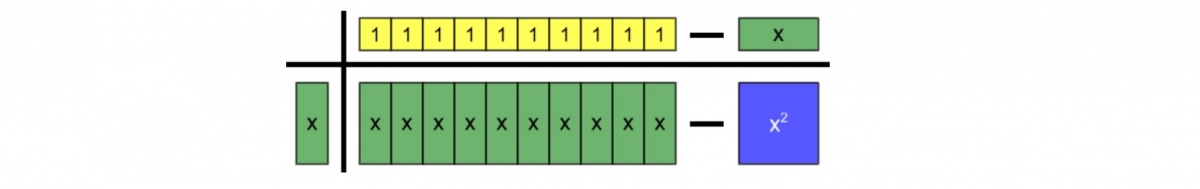

Equations of Type 5 (squares + numbers = roots) have presented the most challenging task in terms of accurate representation of al-Khwārizmī’s verbal descriptions with algebra tiles.3 We thus offer two alternatives for modeling al-Khwārizmī’s first example of this case (taken from [Rosen 1831, 11–12]). Unlike equations of Type 4, it is unlikely that all students will come up with either alternative on their own. After allowing for a period of open exploration (either individually or in small groups), the instructor could illustrate one or both of these modeling alternatives (or offer hints as to how students can get started on each). A classroom discussion of the pros and cons of these different approaches could also be of interest.

Example 8a shows the first approach to modeling of al-Khwārizmī’s instructions for this case, where we have enumerated the solution steps for the purpose of discussing the case’s complexities. In this approach, there are two steps where the algebra tile representation includes operations or objects that are not part of al-Khwārizmī’s verbal instructions. First, in Step 3, I simultaneously felt the need to subtract "\(10-x\)" from both sides while extracting the root of \(4\). This transforms the left-hand side (LHS) into a binomial rectangle with \(x-5\) and \(x-5\) as dimension tiles. Then, in Step 4, I made the adjustment of considering the number 4 of the right-hand side (RHS) to be the square of \(-2\), in accordance with the phrase “Subtract this [root of four] from the moiety of the roots, which is five; the remainder is three” [emphasis added]. Otherwise (that is, if the number \(4\) of the RHS was considered to be the square of \(+2\) at Step 4), I would have first gotten the equation’s other solution (which is \(7\)). al-Khwārizmī did give this other solution as well, at Step 6, but no adjustment involving negative quantities is needed in the algebra tile representation at that step.

Example 8a: Squares and Numbers are Equal to Roots (Type 5), modeling via subtraction

In the second modeling alternative for this same equation (shown below as Example 8b), the transfer of the 10 roots that takes place at Step 3 is modeled using negative algebra tiles (“\(-x\)”), rather than the subtraction symbol. Examples 8a and 8b could be taught via a comparative approach to students, in particular those who are prospective teachers, so that they are led to reflect on the advantages and disadvantages of the two approaches. For instance, whereas Example 8a emphasizes the use of the subtraction operation applied to positive quantities, Example 8b seems to emphasize the use of the addition operation applied to negative quantities. This in turn could lead to the discussion of other topics, such as the concept of an additive inverse and its relevance to subtraction.

Example 8b: Squares and Numbers are Equal to Roots (Type 5), modeling via “-x” tiles

Given the complicated nature of the modeling procedure for equation type 5, it could be helpful to offer students a second example to work out. Example 9 thus shows al-Khwārizmī’s second example for this case [Rosen 1831, 56], following the subtraction approach used in Example 8a. This particular example suggests yet another interesting question for class discussion: why did al-Khwarizmi only give one solution (\(x=2\)) to this equation, and not even mention the second solution (\(x= 10\))?

Example 9: Squares and Numbers are Equal to Roots (Type 5)

Notes

3. Type 5 was also the most complicated case for al-Khwarizmi, as suggested by the comments about the special nature of this case in the following excerpt from his treatise [Rosen 1831, 11–12]:

When you meet with an instance which refers you to this case [squares + numbers = roots], try its solution by addition, and if that do not serve, then subtraction certainly will.

For in this case both addition and subtraction may be employed, which will not answer in any other of the three cases in which the number of the roots must be halved.

And know, that, when in a question belonging to this case you have halved the number of the roots and multiplied the moiety by itself, if the product be less than the number of dirhems connected with the square, then the instance is impossible; but if the product be equal to the dirhems by themselves, then the root of the square is equal to the moiety of the roots alone, without either addition or subtraction.

Instructors who wish to extend this exploration could have their students explore what exactly al-Khwarizmi meant here. However, since deciphering his meaning seems like it would be best carried out symbolically rather than with algebra tiles, such an exploration would be tangential to the main thrust of the activity presented in this article.

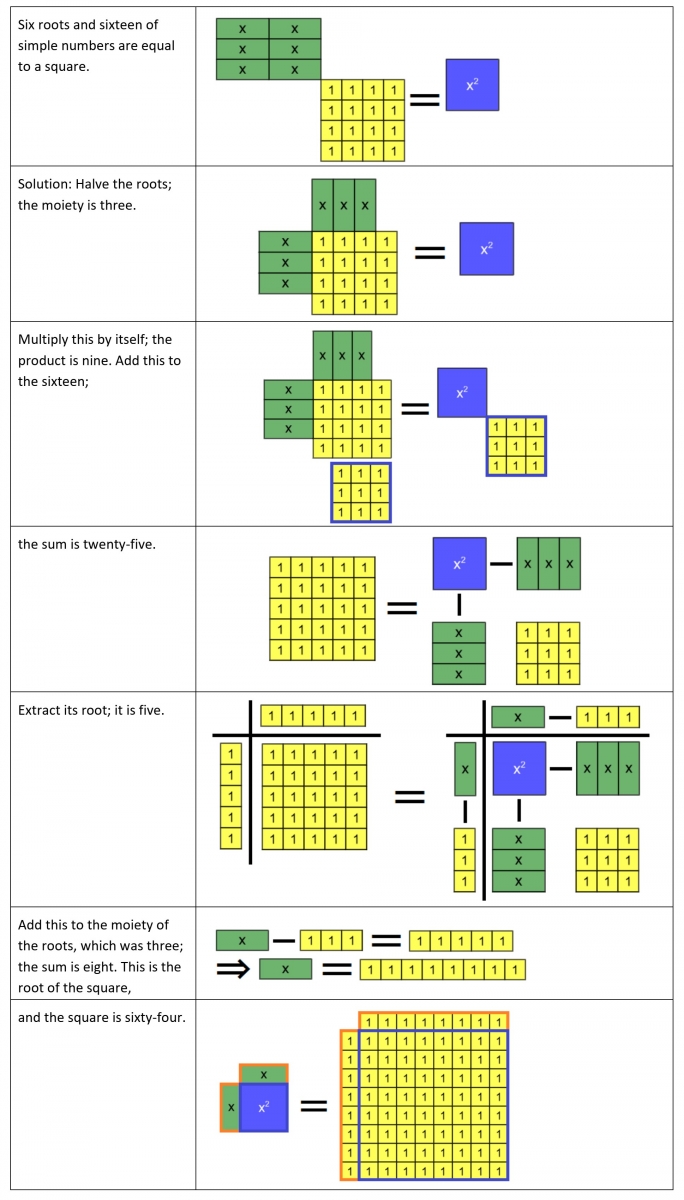

Algebra Tiles Explorations of al-Khwārizmī ’s Equation Types: Roots and Numbers are Equal to Squares

al-Khwārizmī’s sixth and final type of equation can again be modeled using either subtraction or "\(-x\)" tiles; we show only the former alternative. Because the Type 6 equation that was worked out by al-Khwārizmī (“three roots and four of simple numbers are equal to a square”) involves fractions and mixed numbers—which cannot be modeled using algebra tiles—we present a slightly-modified example in its place, following the procedure given in [Rosen 1831, 12]. We also show only the procedure for producing the positive root, as the modification for producing the negative root is analogous to how we proceeded in Example 7.

Example 10: Roots and Numbers are Equal to Squares (Type 6)

Algebra Tiles Explorations of al-Khwārizmī ’s Equation Types: Modeling al-Khwārizmī’s More Complicated Problems

Following his treatment of the solution procedures for each of the six cases of equation, al-Khwārizmī went on in his treatise to present six problems “which will serve to bring the subject nearer to the understanding, to render its comprehension easier, and to make the arguments more perspicuous” [Rosen 1831, 35]. These problems were followed by a large collection of “various questions” that further illustrated how al-Khwārizmī’s procedures for “calculating by completion and reduction must always necessarily lead you to one of these cases” [Rosen 1831, 35]. In the examples below, we illustrate how to model such problems using algebra tiles. We have selected these particular examples in part because they avoid the use of fractions and mixed numbers, yet show the complexity of the equations that al-Khwārizmī treated. Because some problems involve the difference of two quantities, note that it is very natural to use subtraction within the algebra tile models. Following al-Khwārizmī’s advice to his readers that they should “reduce this [equation] according to the rules, which I have above explained to you” [Rosen, 1831, 51], we have omitted the algebra tile representations for some of the later details in our last two examples.

- Example 11: A problem leading to the case “squares = numbers”

- Example 12: A problem leading to the case “squares = numbers"

- Example 13: A problem leading to the case “squares = roots”

- Example 14: A problem leading to the case “squares and numbers = roots”

- Example 15: A problem leading to the case “squares and numbers = roots”

Algebra Tiles Explorations of al-Khwārizmī ’s Equation Types: Modeling al-Khwārizmī’s More Complicated Problems – Example 11

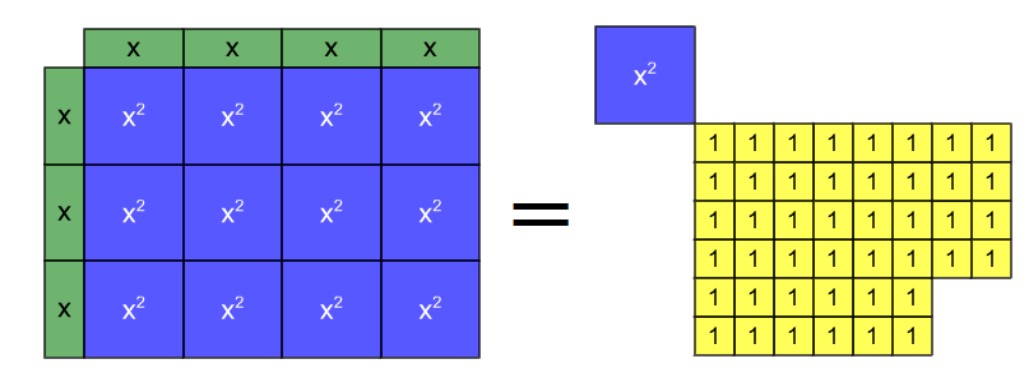

Example 11: A problem leading to the case “squares = numbers” [Rosen 1831, 55]

To find a square, four roots of which, multiplied by three roots, restore the square with a surplus of forty-four dirhems, then the solution is: that you multiply four roots by three roots, which gives twelve squares, equal to a square and forty-four dirhems.

Remove now one square of the twelve on account of the one square connected with the forty-four dirhems. There remain eleven squares, equal to forty-four dirhems. Make the division, the result will be four, and this is the square.

Continue to Example 12.

Back to Overview of al-Khwārizmī’s More Complicated Problems.

Algebra Tiles Explorations of al-Khwārizmī ’s Equation Types: Modeling al-Khwārizmī’s More Complicated Problems – Example 12

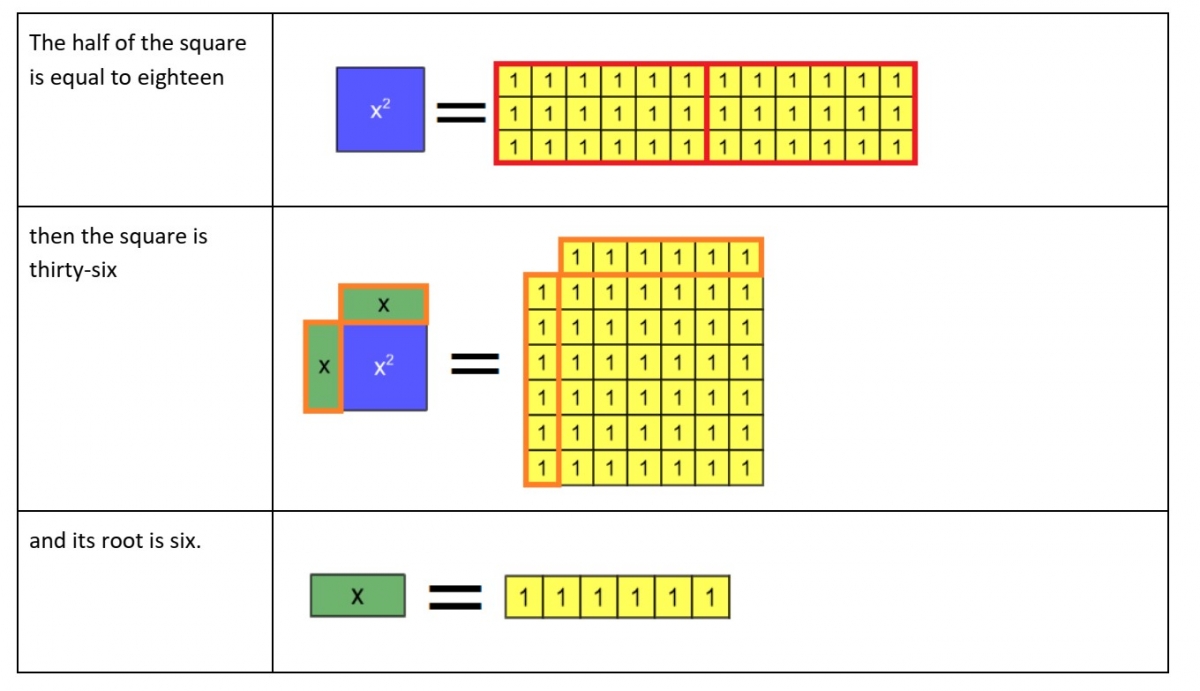

Example 12: A problem leading to the case “squares = numbers” [Rosen 1831, 55]

A square, four of the roots of which multiplied by five of its roots produce twice the square, with a surplus of thirty-six dirhems; then the solution is: that you multiply four roots by five roots, which gives twenty squares, equal to two squares and thirty-six dirhems.

Remove two squares from the twenty on account of the other two. The remainder is eighteen squares, equal to thirty-six dirhems. Divide now thirty-six dirhems by eighteen; the quotient is two, and this is the square.

Continue to Example 13.

Back to Overview of al-Khwārizmī’s More Complicated Problems.

Algebra Tiles Explorations of al-Khwārizmī ’s Equation Types: Modeling al-Khwārizmī’s More Complicated Problems – Example 13

Example 13: A problem leading to the case “squares = roots” [Rosen 1831, 35–36]

I have divided ten into two portions; I have multiplied the one of the two portions by the other; after this I have multiplied the one of the two by itself, and the product of the multiplication by itself is four times as much as that of one of the portions by the other.

Computation: Suppose one of the portions to be thing, and the other ten minus thing: you multiply thing by ten minus thing; it is ten things minus a square.

Then multiply it by four, because the instance states "four times as much." The result will be four times the product of one of the parts multiplied by the other. This is forty things minus four squares.

After this you multiply thing by thing, that is to say, one of the portions by itself. This is a square, which is equal to forty things minus four squares.

Reduce it now by the four squares, and add them to the one square. Then the equation is: forty things are equal to five squares;

and one square will be equal to eight roots, that is, sixty-four;

the root of this is eight, and this is one of the two portions, namely, that which is to be multiplied by itself.

The remainder from the ten is two, and that is the other portion.

Thus the question leads you to one of the six cases, namely, that of “squares equal to roots.”

Continue to Example 14.

Back to Overview of al-Khwārizmī’s More Complicated Problems.

Algebra Tiles Explorations of al-Khwārizmī ’s Equation Types: Modeling al-Khwārizmī’s More Complicated Problems – Example 14

Example 14: A problem leading to the case “squares and numbers = roots” [Rosen 1831, 39–40]

I have divided ten into two parts; I have then multiplied each of them by itself, and when I had added the products together, the sum was fifty-eight dirhems.

Computation: Suppose one of the two parts to be thing, and the other ten minus thing. Multiply ten minus thing by itself; it is a hundred and a square minus twenty things.

Then multiply thing by thing; it is a square.

The sum is a hundred, plus two squares minus twenty things, which are equal to fifty-eight dirhems.

Take now the twenty negative things from the hundred and the two squares, and add them to fifty-eight; then a hundred, plus two squares, are equal to fifty-eight dirhems and twenty things.

Reduce this to one square, by taking the moiety of all you have. It is then: fifty dirhems and a square, which are equal to twenty-nine dirhems and ten things.

Then reduce this, by taking twenty-nine from fifty; there remains twenty-one and a square, equal to ten things.

Halve the number of the roots, it is five; multiply this by itself, it is twenty-five; take from this the twenty-one which are connected with the square, the remainder is four. Extract the root, it is two. Subtract this from the moiety of the roots, namely, from five, there remains three.4 This is one of the portions; the other is seven. This question refers you to one of the six cases, namely “squares and numbers equal to roots.”

Continue to Example 15.

Back to Overview of al-Khwārizmī’s More Complicated Problems.

Notes

4. Note that “twenty-one and a square, equal to ten things” is a Type 5 equation that can be modeled using the procedure from the section "Squares and Numbers are Equal to Roots"; therefore, the algebra tile representations of these final steps have been omitted.

Algebra Tiles Explorations of al-Khwārizmī ’s Equation Types: Modeling al-Khwārizmī’s More Complicated Problems – Example 15

Example 15: A problem leading to the case “squares and numbers = roots” [Rosen 1831, 51]

I have divided ten into two parts; I have multiplied the one by ten and the other by itself, and the products were the same; then the computation is this:

You multiply thing by ten; it is ten things. Then multiply ten less thing by itself; it is a hundred and a square less twenty things, which is equal to ten things.

Reduce this according to the rules, which I have above explained to you.

Continue to Classroom Implementation and Concluding Remarks.

Back to Overview of al-Khwārizmī’s More Complicated Problems.

Algebra Tiles Explorations of al-Khwārizmī ’s Equation Types: Classroom Implementation and Concluding Remarks

It is worth noting that al-Khwārizmī gave geometrical demonstrations for his solution methods for the compound equations (Types 4–6) in order to “point out the reasons for halving” [Rosen 1831, 13]. The figures he gave for equations of Type 5 and Type 6 do not, however, seem to be translatable to an algebra tile representation. Despite this and other limitations of algebra tiles (e.g., the impossibility of yielding an accurate representation of situations involving fractions), the translation of al-Khwārizmī’s verbal descriptions of his procedures to algebra tiles representations offers a multi-representational approach to equation solving that encourages diversity in algebraic reasoning and can promote reflection about its teaching.

The modeling activity proposed in this article can be implemented in an exploratory approach that prompts students to make meaningful and accurate connections between al-Khwārizmī's excerpts and the corresponding algebra tiles representation. After a basic introduction to the use of algebra tiles, the class can work individually or in small groups on Examples 1–10. To guide this work, students can be provided with a two-columned worksheet that gives the excerpts from al-Khwārizmī in the left column and asked to generate algebra tiles representations that model those excerpts in the corresponding “algebra tiles workspace” in the right column; the tables provided in this article for those examples thus serve as an “answer key” for this activity. The initial use of a multiplication mat that physically separates the dimension tiles from the binomial rectangles could be helpful in preventing any potential confusion about the dimension tiles (linear type quantities) and the binomial rectangles (area type quantities). Other obstacles or challenges that the students might encounter for particular equation types (e.g., the necessity of using either the subtraction symbol or “\(-x\)” tiles for Type 5 equations) have also been mentioned in earlier sections of this article. Whole-class discussion and instructor demonstrations may be valuable at certain junctures to overcome those challenges. Instructors who wished to extend the exploration further could then have students engage with the more complicated problems presented in Examples 11–14.

Depending on the student audience and the goals of the instructor, students could additionally be prompted to reflect on and discuss various aspects of the activity. For example, pre-service and practicing secondary teachers could be asked to focus on various components of the algebra tiles representations, such as the role of the dimension tiles, the emerging binomial rectangles, the area conservation principle, and the dynamics of viewing the binomial rectangle area alternately as a sum and as a product. Students in a history of mathematics course might be prompted to reflect on the differences between the mathematical context and assumptions that informed al-Khwārizmī’s work and those that inform today’s algebraic practices that are perhaps better captured by the algebra tile representations. Students in both these groups, as well as high school students and others, might also profitably discuss specific mathematical questions that emerge from the activity, such as whether and why Type 4 and Type 6 equations always have one positive and one negative solution.

As desired, the symbolic representation of al-Khwārizmī’s equation types and procedures could furthermore be brought into the exploration and juxtaposed against both al-Khwārizmī’s verbal descriptions and their algebra tile representations. A discussion of the roles of these different types of representations in supporting student learning of algebra—and especially the pedagogical benefits to be derived from the concrete visualization afforded by algebra tile manipulatives—could be especially fruitful with prospective and practicing secondary mathematics teachers. In these and other ways, the use of algebra tile manipulatives to explore al-Khwārizmī’s procedures opens up new avenues of influence for his Al-Kitab almukhtasar fi hisab al-jabr wa’l-muqabala.

Algebra Tiles Explorations of al-Khwārizmī ’s Equation Types: References, Acknowledgements and About the Author

References

Rosen, Frederic, trans. and ed. 1831. The Algebra of Mohammed ben Musa [al-Khwārizmī]. London: Oriental Translation Fund.

Otero, Daniel E. 2019. Completing the Square: From the Roots of Algebra, A Mini-Primary Source Project for Students of Algebra and Their Teachers. Convergence 16 (September). DOI:10.4169/convergence20190901.

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to thank the Convergence editorial board and anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments on earlier drafts.

About the Author

Günhan Caglayan (MR Author ID: 1116420) teaches mathematics at New Jersey City University. His main interests are mathematical visualization and student learning through modeling and visualization.